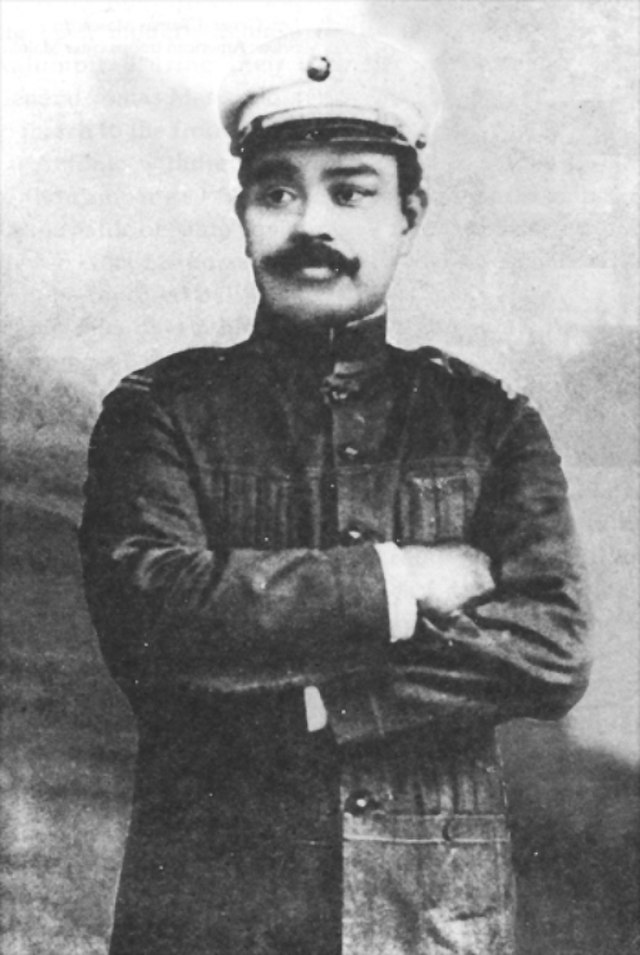

Antonio Luna was born to an ilustrado family from La Union but their family moved to Binondo sometime in 1861 when his father engaged in business as a merchant. He was the youngest in the family. His eldest brother was the famous Filipino painter, Juan Luna. Like Juan, Antonio was a man of the arts for he had a degree in literature.

Indeed, Antonio was a man of diverse interests and intellectual pursuits for he was also a man of science, having had a degree in Pharmacology and Chemistry first from the Ateneo Municipal and later, from the University of Santo Tomas. He studied and did research at the Tropical and Communicable Diseases at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France.

At the same time, Antonio was a sportsman. He was a sharpshooter and he organized a group of fellow sharpshooters called the Luna Sharpshooters. He studied fencing and swordsmanship and was reported to have practiced fencing with Rizal while they were both living in Paris. But later, Antonio also formally studied guerilla warfare and military science.

A man of passion and of a fiery temper (like his brother Juan), Antonio was said to have courted a woman named Nellie Boustead in Paris. He and Rizal were rivals for the affection of Ms. Boustead but Antonio was convinced that Ms. Boustead favored Rizal more. Antonio challenged Rizal to a duel but they were prevailed upon by friends not to duel.

Antonio had no revolutionary aspirations in 1890 when he first left the Philippines to study in Spain. At heart, he was a reformer. He had become a Mason and joined the Propaganda Movement while he studied in Spain and in France. He wrote political essays for La Solidaridad and later became its editor.

Curiously, Antonio refused to join the Katipunan. But in an ironic turn, when the Philippine Revolution broke out in 1896, Juan and Antonio were charged with complicity in the revolution. He and his brother Juan were imprisoned at the Fort Santiago where they denied membership in or sympathy with the Katipunan. It was said that Juan was immediately released from Fort Santiago because he had influential friends who intervened with the colonial authorities on his behalf but Antonio was not released.

While detained Antonio was interrogated about his writings in La Solidaridad. It was reported that he recanted all the ideas he had expressed and proclaimed in his writings in La Solidaridad. Some historians even say that Antonio gave the Spanish colonial authorities what little information Antonio had about the Katipunan and its membership. Still, Antonio was not released.

Curiously, Antonio refused to join the Katipunan. But in an ironic turn, when the Philippine Revolution broke out in 1896, Juan and Antonio were charged with complicity in the revolution. He and his brother Juan were imprisoned at the Fort Santiago where they denied membership in or sympathy with the Katipunan.

Instead, he was exiled to Spain in 1897 and imprisoned. He was tried by a military court in Spain that later dismissed all charges against him. At that time, Antonio realized that armed revolution was no longer avoidable. He studied military science to prepare himself for leadership in the Revolution.

He arrived in the Philippines in 1898 and became an elected representative to the Malolos Congress. He ran for President of the Malolos Congress but lost. He established a military academy to prepare Filipino officers in the conduct of war. He was appointed as the successor of Gen. Artemio Ricarte as the Chief of Staff of the Filipino Armed Forces and later, Director of War under the revolutionary government of Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo.

In Manila, at the height of the Philippine-American War, Luna published his own newspaper La Independencia. He continued to write news stories, commentaries, essays and poetry while he led successful campaigns against Spanish, and later, the American forces during the Philippine-American War.

However, Antonio’s fiery outbursts of temper and confrontational style of leadership did not gain him friends. In fact, those closest to Aguinaldo refused to recognize the leadership of Luna. He had an ambitious plan to retake Manila from the Americans that was undermined by the insubordinate leaders of the Kawit units. They refused to charge the Americans even after Luna had issued the command to charge. Luna stripped these Kawit units of their arms because of their insubordination but Aguinaldo later reinstated them. This factionalism among the revolutionary forces was one of the reasons for the disorganization of the Philippine forces and their subsequent military losses.

He had an ambitious plan to retake Manila from the Americans that was undermined by the insubordinate leaders of the Kawit units. They refused to charge the Americans even after Luna had issued the command to charge. Luna stripped these Kawit units of their arms because of their insubordination but Aguinaldo later reinstated them.

It was asserted by many historians that the Kawit officers and other members of Aguinaldo’s cabinet began rumors accusing Luna of undermining Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo’s authority and of conspiring to oust him in a coup d’état.

The rumors could not be quelled because Antonio was increasingly at odds with Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo. First, Antonio refused to pull out Filipino troops from their position outside the Intramuros, insisting that they take Intramuros from the Spaniards. Luna refused to cede their positions to the Americans but at that time, Gen. Aguinaldo was of the mind that the American forces were there to help the Filipinos defeat Spain. Aguinaldo ordered the Filipino troops to stand down and abandon their positions.

While Aguinaldo was increasingly indecisive and vacillating, Luna was impassioned. Luna advised Aguinaldo to employ guerilla warfare against the Americans to make up for the Filipino forces’ lack of guns and ammunition. But Aguinaldo was already desirous to make peace with the Americans because they had superior military resources.

When Gen. Aguinaldo sought a conference with the Americans through the Filipino Commission to negotiate for Filipino independence under an American protectorate, Antonio vociferously urged action against the Americans and against what he suspected was an American annexation of the Philippines in disguise. Antonio’s fears and insight into the ulterior motives of the Americans were proved valid when the Treaty of Paris came into effect. Through the Treaty of Paris, Spain ceded the Philippines, Mexico and Cuba to the United States and the United States annexed the Philippines.

By the time Antonio had mustered enough troops and materiel, the members of the Aguinaldo cabinet had all but abandoned the idea of Philippine independence and would rather seek peace with the Americans through the Schurman Commission. Luna branded the members of the cabinet as traitors and accused them of seeking peace with the Americans only to secure influential positions under the proposed American civil government. He arrested them but again, Aguinaldo released the cabinet members that Luna had arrested.

By the time Antonio had mustered enough troops and materiel, the members of the Aguinaldo cabinet had all but abandoned the idea of Philippine independence and would rather seek peace with the Americans through the Schurman Commission. Luna branded the members of the cabinet as traitors and accused them of seeking peace with the Americans only to secure influential positions under the proposed American civil government.

The private letters of Aguinaldo which were discovered and published decades later indicated that Aguinaldo had been investigating the alleged coup d’état planned by Luna. He had been writing to officers in the field, confirming their support and loyalty for him. Aguinaldo purportedly sent Luna a telegram in Bayambang, Pangasinan and asked him to meet him at Aguinaldo’s headquarters in Cabanatuan.

When Luna arrived, Aguinaldo was not there. Luna was then shot by the Kawit company of Aguinaldo’s presidential guard in Aguinaldo’s headquarters in Cabanatuan. This was the same Kawit company that Luna had earlier stripped of their arms and arrested for insubordination. Luna was shot and stabbed. His body bore 40 wounds. Luna was buried with full military honors but the Kawit company was never questioned, investigated, or punished for having killed Antonio Luna. The members of Aguinaldo’s cabinet later issued circulars that denounced Luna’s alleged traitorous plan to oust Aguinaldo.

Apolinario Mabini later wrote in his memoirs that Gen. Antonio Luna alone would have been able to instill discipline in the troops had his actions been supported by Gen. Aguinaldo. Mabini intimated that Gen. Aguinaldo by that time was threatened by Luna’s popularity. Mabini claimed that Aguinaldo had a boundless appetite for power as evidenced by his having previously ordered the execution of Andres Bonifacio to rid himself of a rival for power.

Mabini claimed that Aguinaldo had a boundless appetite for power as evidenced by his having previously ordered the execution of Andres Bonifacio to rid himself of a rival for power.

Aguinaldo’s lust for power was manipulated and his suspicion of Luna was stoked by the members of Aguinaldo’s cabinet who were Luna’s personal enemies. Mabini concluded that when in the end, the very soldiers loyal to Aguinaldo and Aguinaldo alone shot Luna to death, Aguinaldo effectively rid himself of his ablest general who was dedicated to pursuing independence at all cost.