All stories have beginnings if they are to make any sense. Some stories open in the middle, others even open near the very end. But regardless of where stories open, every story references a beginning.

In the same way, every nation and culture have a preferred origin story. Virgil wrote the Aeneid to connect the Roman people with what remained of the Trojans after the sack of Troy in Homer’s Iliad. Through Virgil’s work of fiction, he explained the bitter rivalry of the Romans with the Greeks and thus, created a legacy which all Romans could claim. He named Aeneas as the first true Roman hero, though Rome did not even exist in Aeneas’ time.

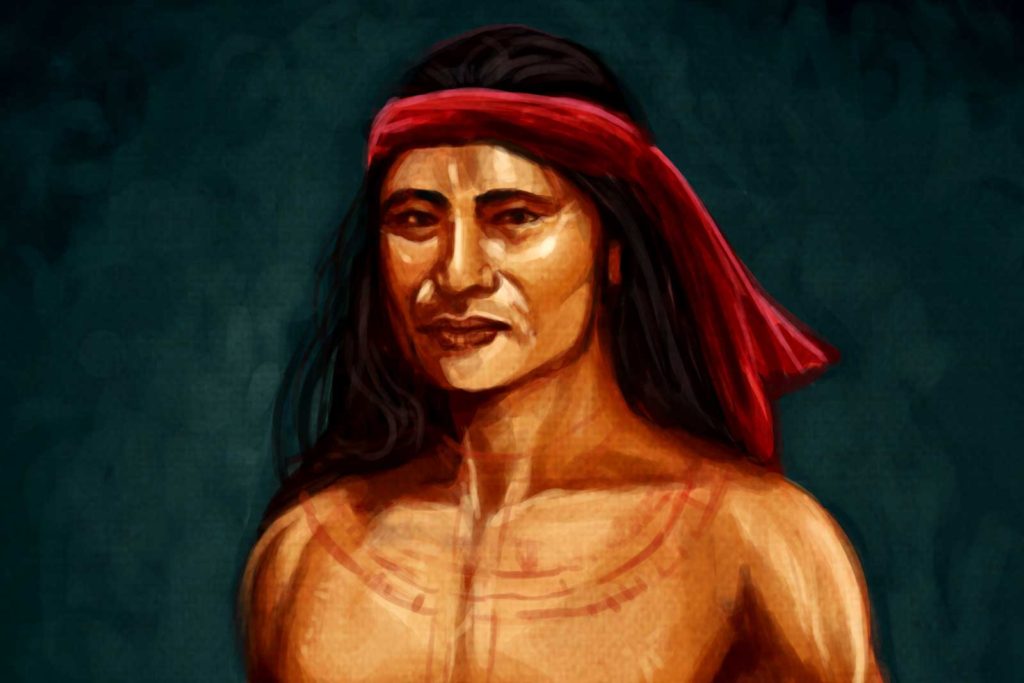

Filipinos celebrate Lapu-Lapu as the first of many Filipino heroes.

The same myth-making process brought Lapu-Lapu into the pantheon of Filipino heroes. Filipinos celebrate Lapu-Lapu as the first of many Filipino heroes. Like Aeneas who lived and died way before the city-state of Rome existed, Lapu-Lapu is claimed by Filipinos as their hero even when the Philippines and Filipinos did not even yet exist during Lapu-Lapu’s lifetime. Just the same, he is still the Filipinos’ preferred origin story, the story of the valiant Filipino spirit.

Yet even with this monumental role as the first Filipino hero, little is truly known of him. His birth and death are unknown, his line of descent is equally obscure. Folk accounts passed through oral tradition situate Lapu-Lapu as the son of Datu Mangal, a ruler of the Subguanons of Opong. Opong is the pre-colonial name of the island of Mactan.

Other stories label him as a migrant from Borneo, who settled on the island. Information regarding his appearance and life are conjectures from colonial accounts detailing the culture of the peoples of the surrounding area. From these accounts, it may be surmised that Lapu-Lapu practiced some form of animism and that he was tattooed.

The primary source of his name and existence is in Antonio Pigafetta’s manuscripts. Pigafetta was the chronicler of Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage. Pigafetta named Lapu-Lapu as one of two chiefs of the island of Mactan.

Even with Pigafetta’s account, Lapu-Lapu’s age at the time he repelled Magellan and his troops is not known. In fact, there seems to be no primary record from any of the surviving voyagers of what he looked like. But Lapu-Lapu’s appearance in the national imagination is that of a warrior in his prime: rippling muscles, tattoos all over his body—someone fierce, someone strong.

There are no direct records of his words of defiance nor any record of him being present at all on the Battle of Mactan—his supposed greatest accomplishment.

In contrast, a lot more is known about his adversary, Ferdinand Magellan. He was a Portuguese sailor who wanted to find a new route to India. When Manuel I of Portugal rejected his proposed expedition, Magellan renounced his nationality and turned to the Spanish king, Charles I.

Under the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, Portugal controlled the route to Asia which went around Africa. With this in mind, Magellan proposed reaching the east by going west. This was a voyage no one had yet accomplished. King Charles approved and funded the expedition, and Magellan took five ships with him. They left Spain on September 20, 1519.

History records Magellan’s landing in the Philippines on March 16, 1521. He believed that he had reached the famed Spice Islands of Moluccas. In fact, he reached the island of Limasawa, on the southern tip of Leyte. There, he began to convert natives to Catholicism and took stock of what trade could be had with the area.

Rajah Humabon was one of the first indigenous peoples to be converted to Catholicism. He was the Rajah of Cebu, which was the neighboring island of Mactan. Cebu was a Rajahnate, founded by a prince from the Hindu Chola dynasty in Sumatra. Humabon was baptized by the Spanish conquistadores as Don Carlos, after King Charles I of Spain.

“Rajah Humabon Plaza” by Constantine Agustin is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

While staying in Cebu, Magellan formed a blood compact with Humabon. A blood compact or sanduguan, was the ritual that sealed friendships or treaties, and validated agreements. Contracting parties made a cut on their wrists and mixed their blood in a cup filled with drink, such as wine, and partook in drinking the mixture.

Historians like to dispute on the precise nature of the sandugo between Humabon and Magellan. Some say it commemorated an alliance of two equal parties—Humabon certainly thought so. Some say the sandugo commemorated the Cebuanos’ submission to the Spanish crown—Magellan certainly believed it was.

Magellan possessed a Malay slave, Enrique of Malacca, who acted as translator between the parties. But Enrique spoke Old Malay, which was a language only distantly related to the language spoken by Lapu-Lapu. The translations made by Enrique must have caused more miscommunication than actual communication.

Accounts and opinions also differ on Humabon’s contribution to the battle of Mactan. Some historians assert that when Lapu-Lapu refused to convert to Catholicism and submit to Spanish rule, Humabon purposefully goaded Magellan to battle. They cite Humabon’s desire to be rid of Lapu-Lapu, his rival.

Others surmise that the battle of Mactan sprung from a misunderstanding on Magellan’s part. Since Humabon was the equivalent of a king for Cebu, Magellan assumed that he was also king of Mactan. That may have been true for European society, but Visayan societies were structured along a loose federation of chiefdoms called kadatuhan. And while Humabon was a powerful chief, he did not rule over Lapu-Lapu. To suggest so must have insulted Lapu-Lapu, the Datu of Mactan.

Whatever the motivation or provocation, on April 27, 1521, Magellan sailed to Mactan with a small force of soldiers. Pigafetta described that the surrounding reefs made it impossible for their boats to dock, and the distance put the island out of musket range. Pigafetta remained on the ship, but Magellan and the soldiers walked through the shallows until they reached the shore. There, the battle commenced.

Whether it was arrogance or a miscalculation, the battle was grossly stacked against the Spaniards. They were sea-weary. Their bulky armor weighed them down, and the heat of the day made them slow. They were outnumbered, and Lapu-Lapu’s warriors fought in a manner they didn’t understand. Many of Magellan’s men died, and the rest escaped back to their ships. The battle was over within an hour.

Pigafetta wrote that the indigenous warriors recognized Magellan as the captain, and they attacked him until he was dead. Another explorer of the expedition, Gines de Mafra, wrote that nothing of Magellan’s body survived the battle. Humabon offered a ransom of copper and iron for Magellan’s remains, but Lapu-Lapu kept it as a war trophy.

Lapu-Lapu is certainly a mysterious figure. There is so much that is unknown about the Datu of Mactan. Who was he? What was motivation for resisting Magellan? Did he see the Spaniards as mercenaries Humabon hired to take Mactan? Did he not like that Magellan was converting people to Catholicism? Was he acting out of greed and pride, or to protect his people? Did he fight alongside his men, or did he watch the battle from a distance? We do not know.

Some argue that he does not deserve to be on the list of Filipino heroes, that he ought to be removed—he was, after all, just another Datu defending his land. If Lapu-Lapu was only defending his land and his right to rule, and he is rewarded by being named and remembered as a hero, then the same should be done for every other datu who drove away their rivals.

Some infer that it was just a coincidence that Lapu-Lapu fought Magellan. Lapu-Lapu’s fight was actually with Humabon and Lapu-Lapu only surmised that Magellan came on behalf of Humabon. After all, if Lapu-Lapu had not defeated and killed Magellan, Pigafetta would never have written of Lapu-Lapu.

Finally, some question how Lapu-Lapu can be considered a Filipino hero if even the very idea of a country called the Philippines had not even been thought of at that time. There was no Philippines at that time. It was decades later, in 1565 when Miguel Lopez de Legaspi came to the Philippines that he claimed the entire archipelago for the crown of Spain and named the archipelago “Felipinas” in honor of Felipe, King of Spain.

2021 marks the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Mactan. Many events have taken place in Philippine history since that day on the beach in 1521. Philippine history is rife with foreign rule and insurgency, and many men and women have risen to the rank of hero. While it is easy to question the validity of Lapu-Lapu’s status as a hero in comparison to others such as Bonifacio or Rizal, Lapu-Lapu’s resistance against the first Spanish attempt of colonization is a fixed point in the story of the Philippine people. Certainly, there were others who came before him, their names and deeds forgotten. Until someone finds records of their contributions, Lapu-Lapu and the Battle of Mactan is a good place to start.

Sources:

Lach, D. F. (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery. Book 2. University of Chicago Press.

Macachor, C. C. (2011). Searching for Kali in the Indigenous Chronicles of Jovito Abellana. Rapid Journal, 10(2).

Ocampo, A. (2018) Lapu-Lapu, national hero. Inquirer.net. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

Ocapmo, A (2019) Lapu-Lapu, Magellan and blind patriotism. Inquirer.net. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

Pinkerton, J. (1812). A general collection of the best and most interesting voyages and travels in all parts of the world (Vol. 12). Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme (etc.).

Scott, W. H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press.