Domestic workers are those who render work within the context of a home, whose labor is necessary and desirable to the health, wellbeing and function of a household. Included in the class of “domestic worker” are cooks, nannies, family drivers or chauffeurs, gardeners, and housecleaners.

Paid domestic work as a solution to working women’s second shift

Arlie Hochschild asserts that in highly developed societies such as in the United States, working women pull a double shift—they work at their jobs or careers from 9-5 and then when they come home, they put in four or five more hours of cooking, cleaning, laundry, and assisting their children with their homework before putting them to bed and preparing meals for reheating for the next day. Some women lose pay and promotion opportunities because they also fulfill caring duties for family members who are ill or disabled.

To cope with this burden, some use the strategy of hiring other women to do the housework while they are away. Some even hire other women to care for their children while they work. Sociologists in the US point to the need for domestic workers in American households because of the lack of affordable housing near the workplace and the lack of affordable day care for women of lower income.

Domestic work as a source of employment for Filipinos

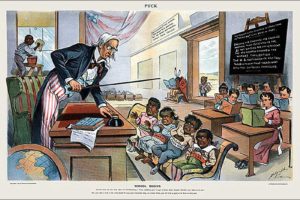

In the Philippines, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that domestic work is a chief source of employment for Filipino women in the Philippines and abroad. Indeed, teenaged girls barely out of high school often work in the cities as domestics for the privilege of going to night classes as college students. Poor relations seeking better education or employment prospects often start as domestic helpers in their richer relatives’ homes in the city. Mothers unable to find work in their provinces other than farming often leave their families to go to the city to work as a domestic helper. This is not a new trend.

Cultural and historical roots of paid domestic labor

Historically, the well-to-do pre-colonial Filipinos of the maginoo or datu classes had aliping namamahay, people who provided domestic work either because they were spoils of war or conquered peoples, or they were people who owed money and must then repay the debt with servitude. As a matter of practice, the aliping namamahay could not be bought or sold by the master and they could own property because they were generally paid by their masters. Eventually, they could earn enough money to buy their freedom and choose whom to marry. The practice of employing domestic help is historically embedded in Filipino culture and history as part of everyday life. Even families of modest means in the Philippines have domestic workers.

Another reason why Filipino women are enticed to work as domestics abroad is not just the higher rate of pay when compared to the pay they can receive in the Philippines. Working abroad is a means to provide for the needs of their children but more importantly, working abroad is a means for Filipino women to escape unhappy or abusive marital relationships. There is no divorce in the Philippines and leaving to work abroad is the next best thing. When Filipino women work abroad, they can have their own money and their dependence on abusive husbands, end. Some women actually divorce their Filipino husbands while abroad so that they can marry men from the country where they work. This allows them to get a work permit and stay as permanent legal residents.

Some women actually divorce their Filipino husbands while abroad so that they can marry men from the country where they work.

Servants that care

Since the 1980s and the 1990s, college-educated Filipino women, often with nursing, teaching, or midwife licenses, have left the Philippines to work abroad as nannies and domestics. The first wave of Filipino domestic workers began to work in cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore. And then, Filipino domestic workers began working in homes in the Middle East: in Saudi Arabia and in the United Arab Emirates.

The Filipino domestic workers usually worked for families where both mothers and fathers worked outside the home and someone must mind their very young children who are not in school yet or to help their school-age children with their homework when they do come home from school. Aviv asserts that Filipino domestic workers in particular, are paid to provide motherly attention to young children in place of their mothers. Since then, a lot of Filipino domestic workers, mostly females, provide care for elderly or disabled family members in homes in the United States, Canada, the UK, Australia, Germany, and New Zealand.

The case of Flor Contemplacion in Singapore

Singapore is one country where migrant domestic workers can never achieve the status of permanent legal residence or citizen. The violation of human rights of Filipino domestic workers cannot be illustrated more plainly than in the story of Flor Contemplacion. In the 1990s, Flor Contemplacion was accused of having drowned a Singaporean boy and murdered his nanny, Delia Magat, another Filipino domestic worker. Flor Contemplacion alleged that she was tortured into admitting and confessing to the crimes. She defended herself by saying that she did not kill Magat, the other Filipino domestic worker—it was her employer that had killed her because the child she was caring for accidentally drowned. There was no physical evidence that Flor Contemplacion killed Delia Magat or the boy she was caring for. Despite the utter lack of evidence, Flor Contemplacion was later executed.

The case of Sarah Balabagan in the UAE

In the United Arab Emirates, a 14-year-old Filipino woman left the Philippines to work as a domestic for a family in Dubai. Balabagan was only 14 when she left the Philippines but unknown to her, the recruiter made it appear in her passport and other documents that she was 28 years old. Immediately upon her arrival, she was subjected to unwanted attention of a sexual nature from her male employer. She was trapped, unable to leave the house, unable to ask for help, and she did not know enough Arabic to report the sexual harassment she continuously experienced.

She repelled a sexual assault on her by her employer. She defended herself and stabbed her employer 34 times. She was found guilty of manslaughter and was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment. An appeal by the prosecution called for the death penalty and the teenager was sentenced to death. Following an international outcry, the President of the UAE himself appealed to the family to drop their demand for the death penalty in exchange for the payment of blood money. In a new trial, the Filipino teenager was sentenced to a year in prison (her four years’ imprisonment was counted as time served), 100 cane strokes, and the payment of the blood money. The 100 cane strokes were meted to her over 5 days, 20 strokes each day. And then she was repatriated.

The case of Juliet Buenaobra in Sydney, Australia

Juliet Buenaobra worked for an Iraqi diplomat as a domestic worker. The diplomat was assigned to Sydney, Australia, the diplomat brought Buenaobra along. The diplomat sponsored Buenaobra for a 403 visa (Temporary foreign domestic worker). To apply for the visa, the diplomat asked Buenaobra to sign an employment contract promising a remuneration package of $ 2975 AUD monthly divided into $800 board and lodging, $250 incidental allowances, $125 medical insurance and summer and winter clothing $50 AUD, and a payment of $1750 monthly as required by Australian labor laws. She was also promised to be paid extra for work performed on Saturdays and Sundays. She was also entitled to 15 days of sick leave per year and the employer agreed to shoulder full medical costs during the course of her employment.

When Buenaobra arrived in Sydney, she was made to work up to 40 hours per week. Although her employer opened a bank account for her, her pay was given to her in cash and from the start of her employment, she was underpaid. She had no room of her own and her meager pay was deducted for her medical insurance (which were never provided for her), and also to pay for the cost of her airfare from Singapore to Sydney, and the cost of her visa application.

When Buenaobra went to the Immigration Office to pick up her identification card, an employee informed her of her rights as a private domestic worker. On her first year, she told the immigration authorities that she was being paid as per her employment contract. However, in her second year, she broke down and cried and said that she was not paid at all according to her employment contract.

Buenaobra then asked her employer to deposit her salary into her bank account. The diplomat and the diplomat’s spouse began arguing with Buenaobra, telling her that the immigration checklist did not apply to her and that all entitlements in the contract were “optional.” When Buenaobra insisted, the diplomat terminated Buenaobra’s employment and locked her out of the house. Buenaobra filed a complaint for unjust dismissal and other money claims with the Fair Work Commission. The FWC awarded Buenaobra $20,000 in compensation.

Domestic workers as an invisible work force

Because the work provided by domestic workers are performed inside homes, they are often ignored when governments and legislatures regulate hours of work, pay rate, benefits, and other terms and conditions of work. They do not come to mind as “employees.” Most American households cannot afford to pay for full-time, live-in domestic workers and instead pay hourly or daily for domestic workers’ services. Few babysitters get paid the mandated federal minimum wage for the babysitting work that they perform.

No knowledge about their rights

In countries where there are employment laws that protect domestic workers, often, protective employment laws cannot be enforced because domestic workers and their employers are unaware of their rights and obligations under the law. Some employers would be willing to comply with legal requirements such as giving their domestic worker a room of her own (if she lives in the employer’s home), days off, a set number of hours of work per day, a basic minimum hourly wage, social security, health and medical insurance. But very few employers even think to provide these for their domestic workers. Few domestic workers know how to seek help to enforce their rights.

Rights are often difficult to enforce

While some Filipino domestic workers have an EB3 visa which allows them to remain in the United States as legal permanent residents while they work as domestics, some Filipino domestic workers are undocumented immigrants who entered the US as tourists and remain in the US long after their tourist visas have expired. This class of Filipino domestic workers are more vulnerable because employers know that the domestic workers cannot even demand to be paid the minimum hourly pay rate for fear that their employers might report them to immigration.

Also, in some countries, a work visa is issued dependent on an employment contract—this means that the work and the terms and conditions of the domestic work they provide hinge upon a sponsorship from one employer. Once the employer terminates the contract (with or without cause), the domestic worker’s work permit will expire and their visa, invalided.

And yet, all this peril has not deterred Filipino women from leaving their families and working as domestic workers abroad. Indeed, the ILO estimates that 25% of all OFW who leave the Philippines each year are domestic workers. Official estimates suggest that around 114, 000 Filipino domestic workers are in the US, 130,000 in Hong Kong, 240,000 in Singapore. But these are only the documented domestic workers.

There are no official numbers that includes undocumented Filipino domestic workers. If we take as true the assertion by the ILO that 25% of all OFWs are domestic workers, and 52% of all OFWs are male, then we can infer the true number of Filipino female domestic workers the world over.

The Philippine government says that there are 2.2 million documented Filipino workers. Twenty-five percent of 2.2 million is 550,000. However, international think tanks and non-government organizations say that the true number of Filipino workers working overseas (including undocumented workers) reaches about 10 million. Twenty-five percent of 10 million is a staggering 2.5 million Filipino domestic workers.

Sources:

Aviv, Rachel (2016). “The Cost of Caring,” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/04/11/the-sacrifices-of-an-immigrant-caregiver

Hochschild, A. R. & Machung, A. (2012). The Second Shift. Penguin, 2012

Juliet Buenaobra v Anwar Alesi [2018] FWC 4311

Parrenas, Rhacel S. (2015) Servants of Globalization: Migration and Domestic Work, 2nd ed. Stanford University Press, 2015.

Sandberg, Sheryl. (2013). Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. Random House, 2013.

Sayres, Nicole J. “An Analysis of the Situation of Filipino Domestic Workers.” International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-manila/documents/publication/wcms_124895.pdf