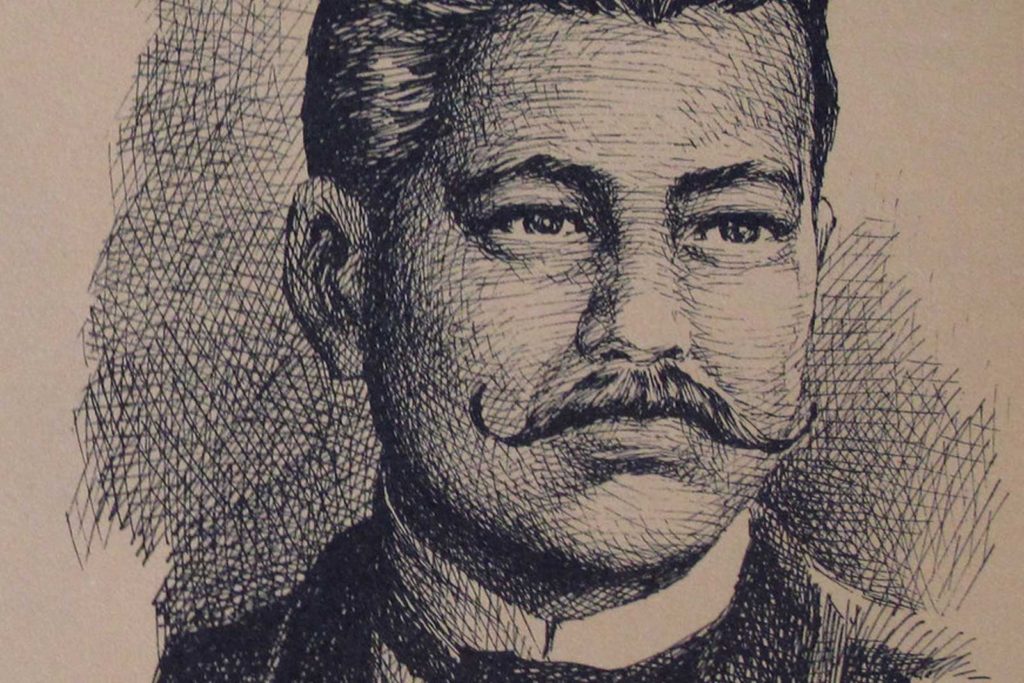

When thinking of Filipino heroes, the mind turns to figureheads of history who were embroiled in the armed struggles at the turn of the twentieth century. Thoughts turn to the likes of Emilio Aguinaldo, Antonio Luna, and Andres Bonifacio. History puts emphasis on the fruits of nationalistic thought over the seeds. And then, when asked about revolutionary writers, the mind turns immediately to Jose Rizal, and after a pause, perhaps then they will finally land on Marcelo H. del Pilar.

Marcelo H. del Pilar was born in Bulakan, Bulacan on the 30th of August 1850. His family belonged to the principalia—the noble and ruling class of educated, upper-class families in the Spanish Philippines. He benefited from their family’s place in society and qualified for higher education. He obtained his bachelor’s degree in 1860 from the Colegio de San Jose, and pursued law and philosophy from the University of Santo Tomas (like Rizal).

History heralds Del Pilar as a writer, a lawyer, a freemason, and the Father of Philippine Journalism. But what is fascinating about del Pilar was the growth of his ideas which mirrored the propaganda movement and the later revolution.

History heralds Del Pilar as a writer, a lawyer, a freemason, and the Father of Philippine Journalism.

Historians label del Pilar’s early movement as anti-friar. In his youth, del Pilar was sentenced to thirty days at the Carcel y Presidio Correcional or the Old Bilibid Prison. This was because, at a baptism where he acted as godfather, he had questioned the excessive baptismal fee charged by the parish priest. But his later writings will show that to call him anti-friar and to call his agitation simply matters of religious contention is simplistic.

For instance, when the troops and laborers of Fort San Felipe in Cavite rose up in rebellion in January 1872, colonial officials and friars agreed that the mutiny could only have been organized at the hands of Filipino priests influencing their flock. The Spanish colonial government decided that to quash dissent, the failed mutineers and many innocent Filipino priests will be deported or executed. The priests Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora, collectively known as the Gomburza, were executed by garrote. Among the exiled was del Pilar’s eldest brother, Father Toribio H. del Pilar, whose expulsion to the Marianas Islands caused the early death of their mother.

Events like these called Del Pilar’s attention to the oppression and exploitation routinely dealt by the Spanish crown on indios through the colonial government and priestly orders such that even the noble illustrados (as in the case of Del Pilar’s brother) were not exempt.

In response, Del Pilar he took up the pen and wrote many articles expounding on acts of oppression and exploitation by the friars and the colonial government. Unlike Rizal, Del Pilar chose to write in Tagalog, not Spanish. He chose the language that was more widely used by his countrymen over what was fashionable. His works were mostly parodies. He used near blasphemous humor to narrate the inequality between the priestly class and the indios.

Works such as Caiigat Cayo (Be Like the Eel) and Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayers and Mockeries), contained humorous and sarcastic anecdotes which reflected a society rigidly and unequally divided by class and ethnicity. They were also published in pamphlet form to make them easier and more affordable to disseminate among the provinces. The indios thought it as entertainment but others saw Del Pilar’s works as food for thought and cause for reflection.

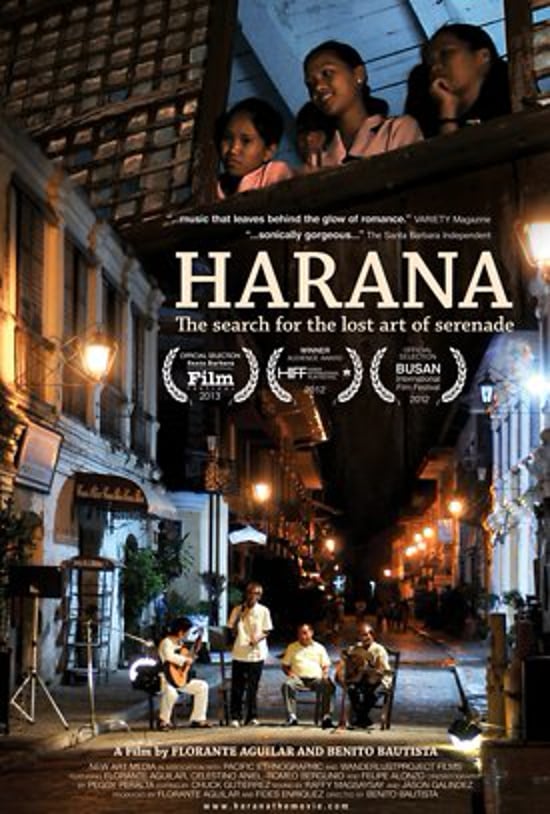

It is important to remember that during this time, the friars of the Augustinian, Dominican and Franciscan orders held executive and control functions on the local levels of governance. They kept the census and tax records, supervised the selection of local officials, supervised education, maintained public morals, and reported incidences of sedition to higher authorities. This was their power over the ordinary folk, the unlettered indios. To go against them was a death wish, and yet that was exactly what Del Pilar did.

Del Pilar lent his advice to the gobernadorcillo of Malolos. At del Pilar’s word, the gobernadorcillo had the town’s friar curate removed when the friar wanted to bloat the tax list for the parish’s financial gain. This is significant. An indio who was appointed as gobernadorcillo (a petty mayor) dared to censure and terminate the Spanish friar, all on Del Pilar’s advice.

Del Pilar advised another gobernadorcillo to arrest a friar who had paraded the body of a cholera victim. Parading a cadaver increased the likelihood of spreading the epidemic and it violated an executive order of the Director General of Civil Administration in Manila regarding the exposition of cholera victims in churches.

Later, Del Pilar wrote a manifesto addressed to the Spanish Queen regent enumerating the crimes of the friars and demanding their expulsion from the country, including Pedro P. Payo, the then Archbishop of Manila.

More than being merely anti-friar, Del Pilar’s writings and actions can be read as part of the movement to remove individuals whose religious office and influence protected them even when they oppressed the indios. One could say that Del Pilar’s sentiments were not anti-clerical, per se, it just so happened that many of the exploitative people simply happened to be friars.

For all Del Pilar’s efforts, in 1888, Valeriano Weyler, the new governor-general of the Philippines issued a warrant of arrest against Del Pilar. He was charged for being a filibuster and a heretic. To avoid imprisonment and execution, Del Pilar left his homeland, his wife, and his children in October 1888 and sailed for Spain. Yet even on foreign soil, he did not cease. He found a group of Filipino students, expatriates, and exiles in Madrid collectively working as the Propaganda Movement. He took up his pen and continued his endeavor of exposing the ills and abuses of the colonial government and the friars.

In December of 1889, del Pilar succeeded Graciano Lopez Jaena as the editor of La Solidaridad. This was the organization and newspaper of Filipino liberals exiled form the Philippines and students attending Europe’s universities. By this time, the illustrados had become sufficiently wealthy to send their sons to Europe to study there.

The aim of the Soli (nickname of the newspaper La Solidaridad) was to increase Spanish awareness to the needs of its colony. Under Del Pilar’s editorship, he expanded the pursuit of Soli to include the assimilation of the Philippines as a province of Spain; the removal of friars and secularization of the parishes; securing for indios the freedom of assembly and speech and equality before the law; and Philippine representation in the Spanish Cortes, the legislature of Spain. These were privileges the indios did not have despite nearly 300 years of Spanish occupation. Del Pilar wrote for the rights of indios, to raise their standard of living and to ready them for future progress.

In Spain, Del Pilar’s ideas and aspirations evolved from assimilation into reform, and eventually to revolution. Del Pilar noticed, however, that while news of the plight of the indios in the Philippines enjoyed the full support of the Filipinos in exile in Spain and gained traction among Spanish citizens, it was ignored by the Spanish crown and government.

Del Pilar’s despondency and melancholy were recorded in his letters to his wife and friends in the Philippines from this period. He longed for home, and for true change. But Del Pilar’s resilience and perseverance were also notable. He continued the publication of La Solidaridad even as funding grew scarce. He reached into his own holey pockets and funded the newspaper himself.

Despite Del Pilar’s effors, on November 15, 1895, La Solidaridad ceased publication. In tandem with the newspaper’s decline was Del Pilar’s descent into extreme poverty. He missed meals, and kept himself warm through winter by smoking cigarettes. It is no surprise that his health deteriorated. He suffered from tuberculosis, much like Lopez Jaena, the editor of La Solidaridad before him. The poverty that hounded their efforts was obvious.

Unable to go back home, Del Pilar began to write to the leaders of the Propaganda movement who had also began founding secret societies dreaming of revolution. Del Pilar wrote to Bonifacio, and approved of the by-laws of the Katipunan. Del Pilar’s personal letters to Bonifacio were even copied down and given as a guide to the Katipunan’s first supreme leader, Deodato Arellano who was Del Pilar’s brother-in-law. To this day, his letters are regarded by historians as important documents of the revolutionary movement.

Del Pilar breathed his last on July 4, 1896, believing that he had failed in freeing his country from clerical abuse and the Spanish colonial system. His death—of disease on foreign soil—would later disqualify him when in 1901, the Philippine Commission searched for a national hero. And while he is often overlooked in favor of other heroes such as Andres Bonifacio and Jose Rizal, there can be no denial of the widespread contribution of his works.

Marcelo H. del Pilar did not fight with the sword, and it is simplistic to say he fought with the pen. He fought with ideas—ideas of inequality, and of liberty, and of change. He wrote 150 essays, 66 editorials, and countless personal letters all dedicated to these ideas. His body of work reflects the belief that widespread societal change roots itself in an awakening of the mind.

Curiously, after the Cavite Mutiny and after the Cry of Pugad Lawin, the colonial government arrested, deported and executed writers and thinkers thinking that they provoked the indios to revolt. And if there were no more writers and thinkers, then the indios who were of lesser intellect would not be able to see their oppression. True enough, the indios rose in revolt because someone opened their eyes to a colonial system designed to keep them subservient and lesser. Marcelo H. Del Pilar and other intellectuals like him opened the indios’ eyes. Because of his writings, the seed of his ideas of freedom bore fruit in the Philippine Revolution.

Sources:

Bernard, M. A (1974). The Propaganda Movement: 1880-1895. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, 22(1-2), 210-211.

Constantino, Renato (1975). The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Quezon City: Tala Publishing Services.

Villarroel, Fidel (1997) Marcelo H. del Pilar at the University of Santo Tomas. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House

Zapanta, Lea S. (1967) The Political Ideas of Marcelo H. del Pilar. Quezon City: University of the Philippines.