In discussing the heroism of Melchora Aquino, we have to reflect on what acts a person must do for their name to go down in history. After all, textbooks are littered with stories of men who gave their lives up for a cause. These men were great men, learned men, visionaries, idealists, and warriors. But what about women—the word “hero” itself refers to males and when women are deemed to have done heroic acts, their sacrifice is barely noticed. Can a Filipino woman be a hero when Filipino society then deemed women’s lives of lesser value than men’s? How much should a woman sacrifice for history to call her “hero”?

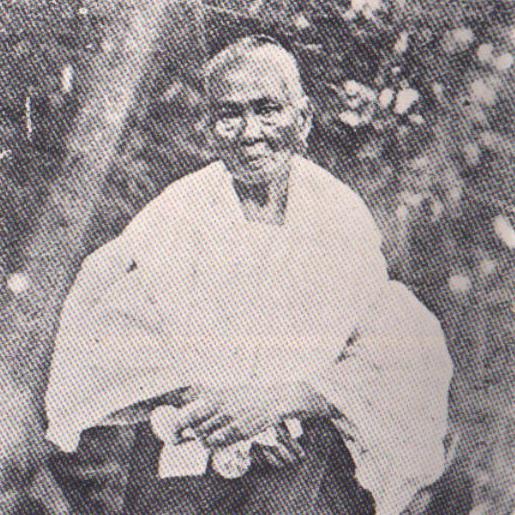

Melchora Aquino was born on January 6, 1812 in Barrio Banlat, Caloocan. In present-day, this area where she was born is named after her: Barangay Tandang Sora, Quezon City.

She was the daughter of a farming couple, and never attended school. In her youth, she was known for maidenly accomplishments: her beauty and her singing voice. She often sang at local fiestas and parties, as well as during mass at church. She was often chosen to lead the Santacruzan. Traditionally, the town’s young and beautiful maidens led the processional pageant as Reyna Elena. The celebration commemorates Empress Helen’s finding of the Cross of Christ, and this has been celebrated in May every year since the Philippine colonial period.

Melchora or “Sora” married Fulgencio Ramos later in her life. He was the cabeza de barrio or village chief—this was one of few occupations in government which indios could hold during the latter part of the Spanish colonial era. Aquino bore her husband six children, and was widowed shortly after the birth of her youngest child.

Aquino had a close connection to Andres Bonifacio. Bonifacio was the Supremo, or the leader of the Katipunan.

Despite being widowed, she looked after their farm and children to the best of her abilities. She also inherited her parents’ farm, and worked to keep it prosperous. As a farmer, she understood the hardships her countrymen experienced. Farmers in those days were heavily taxed for their harvest. They were also made to pay for fiestas in honor of various saints.

Despite having no formal education, she was known to be very intelligent, and literate from an early age. She also assured that her children received the proper schooling she lacked. In her later years, her children would help her in her livelihood and later support her in her old age.

The Spaniards required indias to follow the pattern of European women at the time—they were to be meek and submissive. Women held no important position aside from mother and wife and they controlled nothing aside from her household and her children. All these things that Melchora Aquino had, her household and her children, she gave for the revolution.

Aquino had a close connection to Andres Bonifacio. Bonifacio was the Supremo, or the leader of the Katipunan. The Katipunan was a secret society founded in 1892, whose primary goal was to gain independence from Spain through armed revolution. Bonifacio was a friend of the Aquino family, and he often visited the store Aquino tended to consult with her on the organization’s movements and decisions.

It was Bonifacio and the Katipuneros who called Melchora Aquino by her nom de guerre “Tandang Sora”, a name by which she would be known in the centuries that followed.

Her association with Bonifacio allowed her a deep knowledge of the Katipunan’s plans and operations. She also knew many of his top officers, and her own children eventually joined the movement. History would see her protecting both her offspring and the rest of the Katipunan to the best of her ability.

It was Bonifacio and the Katipuneros who called Melchora Aquino by her nom de guerre “Tandang Sora”, a name by which she would be known in the centuries that followed. Tandang Sora derives from two words: matanda (old person) and Sora, the contraction of pronouncing Melchora (Melsora). These days, to call someone old—especially to their face—is an insult. It offends based on insinuations of senility and inutility. But in those days, attaching the adjective to a name was considered respectful. It acknowledged an age-based seniority, and all the wisdom and experience that came with aging.

The manifestation of respect through her nickname was not unfounded. Despite being 84 at the time, Bonifacio believed her capable of heading a revolutionary movement in her barrio of Balintawak. And she was.

After a scrimmage with Spanish soldiers, she opened her home to the wounded and provided them refuge. She also drew from her granaries, giving aid of 100 cavans of rice (roughly 5000 kilos) and 10 carabaos. The cost of these exceeded several years’ worth of wages, yet she gave them to the cause. And often after similar altercations and battles, she would provide medical aid and offer prayers for the wounded.

In August of 1896, the secret society was betrayed by Teodoro Patino. There are many differing accounts on the motivation of this betrayal but the endpoint is the same. The Spaniards raided hideouts, printing presses, and houses that had connections to the Katipunan. They confiscated documents, maps, and anything else they could find. The Spaniards also arrested and imprisoned anyone suspected to be in league with the Katipuneros, regardless of whether the accused was initiated or not. The secret society was secret no more, and the Katipunan had to act before they were captured and their dream of independence killed alongside them.

In answer to this, Bonifacio ordered a summons for the chapter heads and treasurers of the Katipunan Supreme Council on August 22 to decide their actions. They met at Kangkong—in the house of Aquino’s eldest son. There the majority voted in favor of revolution. To prove their determination, they tore up their cedulas or residence certificates. Those residence certificates were symbols of their subjugation to Spain. Those who did not possess cedulas would not be able to pay taxes, and nonpayment of taxes was an offence for which indios were imprisoned.

Among those who tore their cedulas in defiance were Melchora Aquino and her sons. This event would later be known as the Cry of Pugad Lawin, or the Cry of Balintawak. It would also be the site of the first clash between Katipuneros and the Guardia Civil—it was the start of the revolution.

The next day, to avoid the Guardia Civil who were looking for them, the assembly was moved to Aquino’s property in Banlat. It was there that the Katipunan Supreme Council constituted a revolutionary government and elected leaders as key officials to guide the revolution. It was in Aquino’s barn where the Katipunan transformed from a secret society to the country’s first native government.

This meeting was interrupted by Spanish soldiers, and Aquino and her family fled. While in hiding, she watched the soldiers burn her home and granaries. They caught Aquino when she was hiding out at Pasong Putik, Novaliches. She was transported to the Bilibid prison for interrogation on August 29, 1896.

It is unclear whether she was simply interrogated or if she was tortured as well. Regardless, she gave away nothing. When accused of disloyalty to the Spanish crown and charged with insurgency, she replied, “What was evil about helping those in need, of feeding hungry neighbors and friends of my family?” Aquino also insisted that she had done no wrong in sharing what she had to those that needed it; if she’d had nine lives, she would have given those too.

Aquino was exiled to Guam with 171 others, all of them charged with rebellion and sedition. Once there, she was placed under house arrest. Perhaps this was a weakness or mercy on the Spaniards’ part: they could not—or would not—execute an old woman. Perhaps the Spanish colonial government thought that Tandang Sora was old, and she had lost both her home and her family—what further acts of rebellion could she wage if they deported her? No doubt they thought she would die soon after her exile. But, as it happened, Aquino outlived the Spanish colonial rule.

She did not return to the Philippines until February 26, 1903, after seven years of exile. The Americans offered her a pension and monetary reward for her sacrifices, but she refused. She passed away at the age of 107, on the 2nd of March, 1919.

She was laid to rest in the mausoleum of the Veterans of the Philippine Revolution at the La Loma Catholic Cemetery in Manila. But in 2012, her remains were transferred to its current resting place: the Tandang Sora Shrine, along Banlat Road, Quezon City.

It is not an exaggeration to say that women were largely invisible in the business and history of nation-building. Their deeds are often overlooked, deemed as insignificant, and forgotten. Women were relegated to minor roles such as wife and mother. And many did not regard the epithet of mother as noteworthy.

But a look at Melchora Aquino’s life proves otherwise. Not only was she a strong mother figure to her own children, she was also a mother figure to the revolution. These days, alongside her nickname of Tandang Sora, Melchora Aquino is known as the Mother of the Philippine Revolution. To the question of what can a woman give to be a hero, Melchora Aquino’s life answers loud and clear: A woman will give whatever she has to give for her freedom.

Sources:

Guerrero, Milagros C. and Schumacher, John N. (eds.) Reform and Revolution. Volume 5 of Kasaysayan: A History of the Filipino People. Asia Publishing Company, Ltd., 1998, pp. 166-168.

Language Arts for the Filipino Learners: An integrated Language and Reading Work-a-Text for Grade Four: Volume One. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 106.

Medina, Isagani R. “Melchora Aquino Wife of Fulgencio Ramos. Women in the Philippine Revolution. Quezon City: Printon Press, 1995, pp 12-13.

Ocampo, Ambeth. “Tandang Sora home on her 200th birthday. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved: May 05, 2021.

“The Tandang Sora bientennial.” Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 05, 2021.

Torrevillas, Domini M. “Tandang Sora: Hero of Heroes” From the Stands. Philstar.com. Retrieved May 05, 2021.