Rizal in the US

About a year after Rizal had published his first novel, Noli Me Tangere, in Heidelberg, Germany, he returned to the Philippines but stayed only for six months. The novel exposed the inequality and oppression Filipinos suffered under Spain. The Spaniards who held all secular power in the Philippines, the government and the church, did not approve of the way Rizal portrayed them in his work. Rizal fled to Hong Kong after six months of death threats and persecution in his homeland.

He stayed for a few months in Hong Kong before crossing over to stay in Japan, Rizal intended to make for Europe once more. The trip from the Philippines to Spain by steamboat involved traveling to Japan or Hong Kong before crossing the Pacific to Acapulco. From Acapulco, Mexico, the next leg of the trip was through the Gulf of Mexico, out to the Atlantic and then on to Europe.

Perhaps Rizal was afraid of being arrested by Spanish authorities if he landed in Mexico, or perhaps he just wanted to vary his travel route to Europe. This time, he took a steamer called the Belgic across the Pacific that took him to San Francisco, California. And while the steamer docked in the San Francisco port on April 28, 1888, Rizal did not set foot on US soil until May 4, six days after the Belgic had docked. Rizal and the other passengers were detained due to a supposed outbreak of cholera onboard which he later learned was a false report.

Rizal arrived in the United States at a bad time for immigrants. While the young country was not a stranger to importing cheap laborers, he had come when many citizens of Caucasian ethnicity—in layman’s terms, the Whites—stood against welcoming migrant workers. Locals feared that foreigners would take their jobs and crowd their cities. Politicians running for public office cracked down on immigration, and denied many foreigners entry into the United States to win votes.

Rizal realized that the ship held over 800 Chinese citizens seeking work on the US railroads. The US customs authorities had roped in the Health Department into quarantining all inbound ships from Asia to stop Chinese laborers from getting jobs on the railroads. Those on board protested and a week later, Rizal was allowed to disembark and begin his journey across the North American continent.

The Transcontinental Railroad System

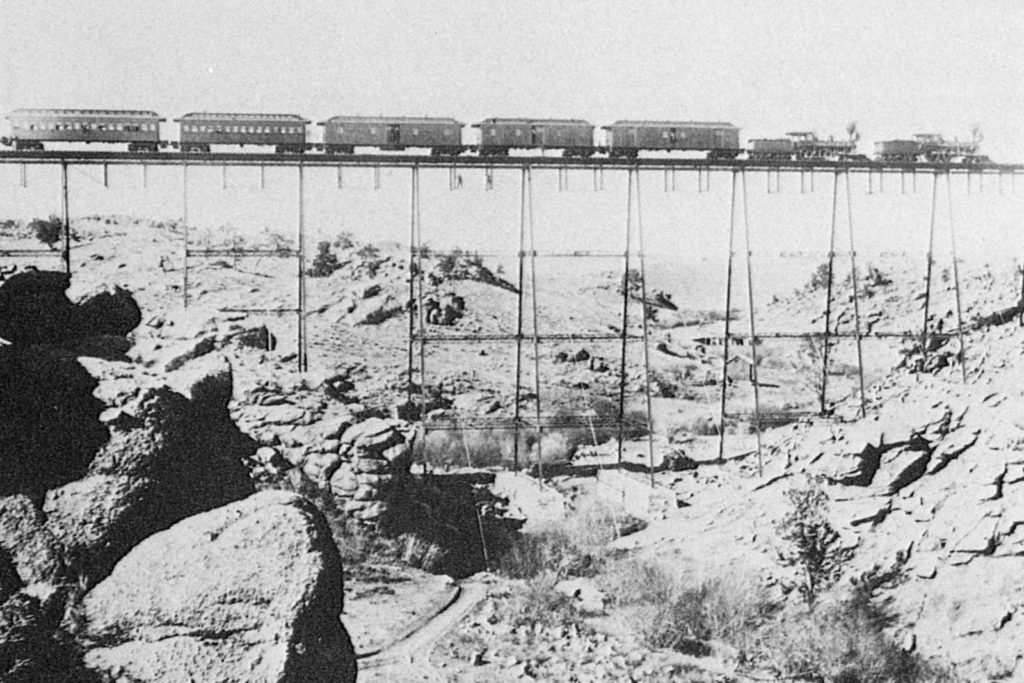

Crossing the entirety of the continental US was difficult in those days. There were no airplanes or airports and there were no cars or buses and no highways. There was no system of highways along which stage coaches could travel. The fastest way to get from the West coast to the East cost of the United States was by train.

In the latter third of the nineteenth century, many independent railroad companies built and ran railroads that connected the towns and cities across the United States. Most sprawled across the more populated eastern coast and delved halfway into the continent, but none provided a segmented line connecting the East coast to the West until 1869.

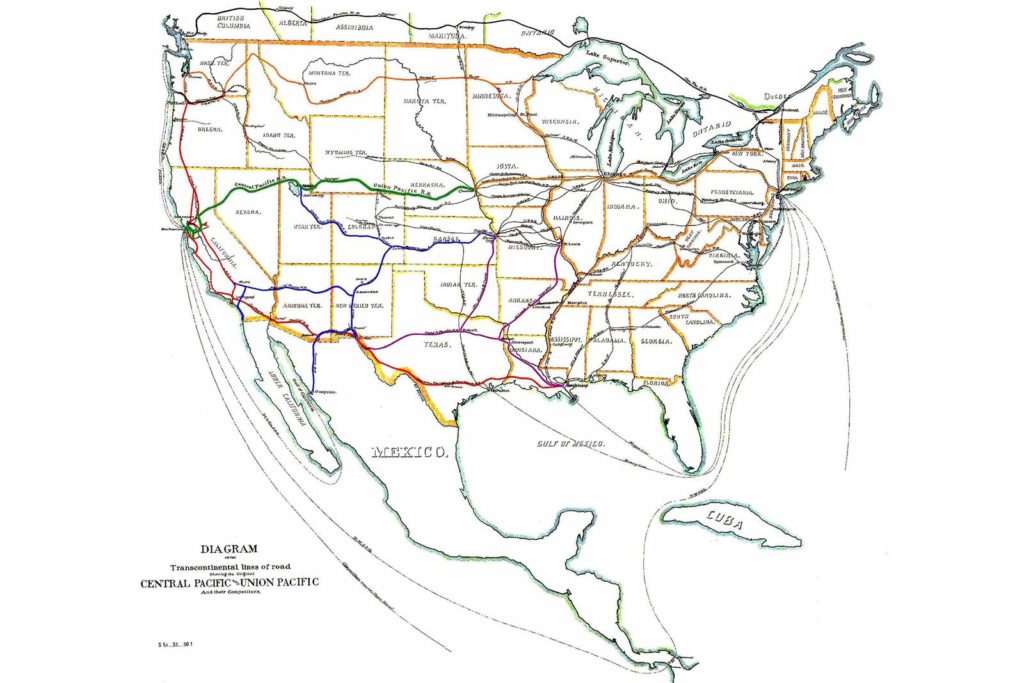

In 1845, Asa Whitney proposed the idea of a railroad with a route from Chicago and the Great Lakes to Northern California. The idea centered around opening up the interior of the continent for several reasons: (1) the ease of transportation of people and goods, (2) allowing the ease of transportation prompted settlement, (3) and settlement of the American frontier would boost business, and the growth of the industrial economy. And while Whitney’s proposal was put on the back burner, legislation eventually circled back to the idea of a transcontinental railroad.

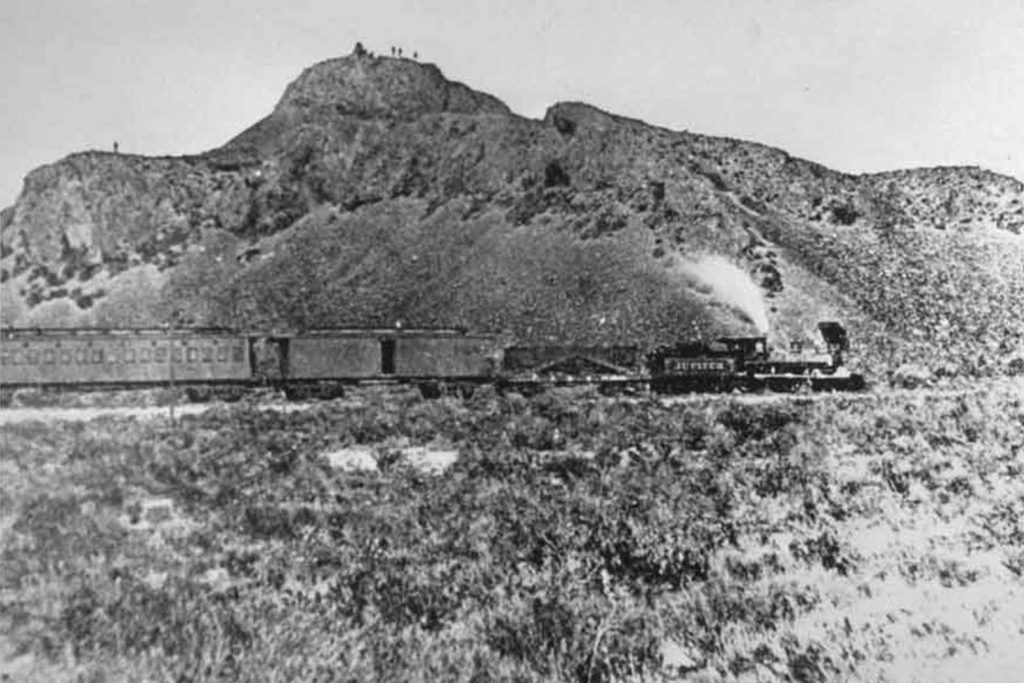

Construction of the railway began in 1863, under the two railroad companies: Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad. The latter began in Sacramento, California and worked eastward. On the other hand, the Union Pacific Railroad Company began from Omaha, Nebraska and built their railway westward. Omaha was already a major hub where the minor railroads of the Union Pacific Railroad Company converged from the eastern seaboard states. The area had previously been chosen by Abraham Lincoln as the location of a Transfer Depot, where up to seven railroads could transfer mail and other goods to Union Pacific trains bound for the west.

The US government contracted both railways and paid them by the mile. Both railways met around the north shore of the Great Salt Lake, in Promontory in what is known as a ‘transfer point’. This transfer point was agreed upon only after construction of both railways passed each other as they worked in opposite directions. Around 1870, the transfer point was moved from Promontory to Brigham City, a better location for servicing trains.

A later merger with the Southern Pacific Railroad built a direct route to the Oakland Long Wharf on San Francisco Bay. This system is what is known in the United States’ history as the Pacific Railroad. Ferries, and then sleighs in the wintertime, were used to transport trains across the Missouri River before they could access the tracks at Omaha. But by 1872, the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge was completed. This is the railroad Rizal took, and his journey from San Francisco to New York harbor lasted only eleven days.

Rizal’s Notable Stops

As anyone who studies Rizal knows, the man recorded his life meticulously through his journals—a habit he’d nurtured since childhood. And through his journals, one may piece together Rizal’s sojourn across the continental US.

San Francisco and the Palace Hotel

Once permitted ashore, Rizal checked-in at the Palace Hotel for two days. The price for lodging was $4, and this included a bath and meals. The hotel was considered quite prestigious and expensive in those days. In his diary, he mentioned that he saw the Golden Gate bridge, and that the stores were closed on Sundays. His diaries also noted a preference for Market Street, a major thoroughfare in the city, and Dupont Street, in Chinatown—which is Gant Avenue today.

On May 6, a Sunday, Rizal checked-out of the Palace Hotel and rode a ferry across the bay for Oakland. There he boarded the first train that would take him east. The entire fare cost him $65.

Sacramento

His diary entries hold that by evening fall of May 6, the train had reached Sacramento. There Rizal had supper and later slept in his coach. By morning, the train had reached Reno, Nevada where Rizal had breakfast. Both meals, hearty by his approximation, cost him only $0.75 cents each.

Reno

He noted that Reno had already been glamorized by propaganda as “The Biggest Little City in the World.” Of Nevada in general, he noted that it was a lonely place; lacking plant-life, with sand everywhere and bare mountains. For a man who spent his childhood in the tropics of Southern Luzon, and then most of his adulthood in Europe, the desert must have shocked him.

Ogden

Of Ogden, Rizal noted that perhaps, with better irrigation, the area might be cultivated. Most of what he saw were fields and cattle. He did note, however that from Ogden to Denver, the clocks on the train and in the stations were set an hour ahead.

He also showed an appreciation for the banks of the Salt Lake, and the mountains in the distance where snow still covered the peaks. Perhaps in a bout of homesickness, he likened the mountains in the middle of the lake with Talim, the island in Laguna de Bay near his hometown. Rizal changed trains at Ogden, which proceeded to pass through two mountains through a narrow channel. Outside the cities and bustling transportation hubs, Rizal noted that most of the countryside was densely populated, even to the point of being lifeless.

Denver

Colorado was the 5th state Rizal visited. By then, it was the 9th of May. There he noted that of the three previous states, Colorado had more trees and horses. The train also moved at an upward incline, where snow and icicles adorned the train’s path.

Omaha and the Missouri River

Rizal described the state of Nebraska as plain. But as for the city of Omaha, he did admit that it was the largest city he’d seen since San Francisco. He marveled at the Missouri River, which he estimated as being twice as wide as the Pasig River at its widest part. He described the area as marshy; and that the train went slowly as it passed over the Missouri bridge before they entered Illinois.

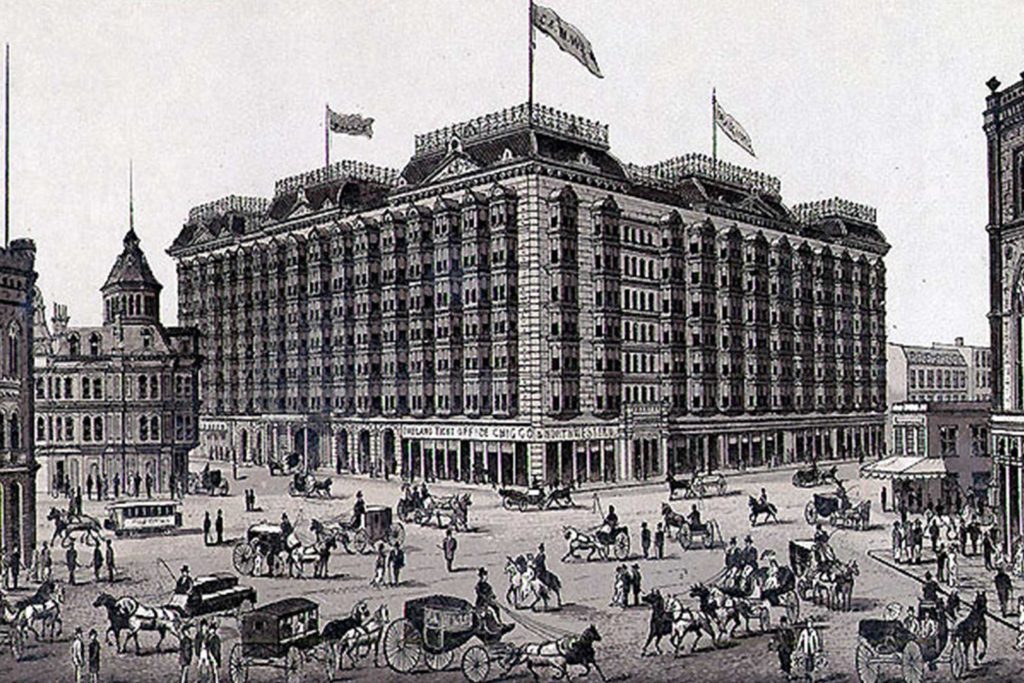

Chicago

By May 11, they had reached Chicago. He did not stay the night, but he likely walked around the city as the train allowed a short layover. From his brief exploration he noted that every tobacco store had an Indian figure. That is to say, he had noted that tobacco stores advertised their wares with images of Native American tribesmen; though, he did not note any consistency as to which the tribe or nation they belonged.

Niagara Falls

The train stopped along the border of Canada on the afternoon of May 12, allowing Rizal to disembark and view Niagara Falls. While amazed at its sheer size, he compared it to the falls of Los Banos. He wrote that the latter was finer and more beautiful, while Niagara Falls was bigger and more imposing. In his letter to Mariano Ponce, he called the falls ‘the majestic cascade’ The train departed at night, and the ‘mysterious sound and persistent echo’ of the Niagara Falls followed him.

Albany and New York City

Once in Albany, Rizal once again noted the sheer size of the city and the Hudson River which the train crossed. He noted the beauty of the place, and of the ships ferrying along the Hudson. It was in New York, on Sunday May 13, 1888, that Jose Rizal’s transcontinental trip ended.

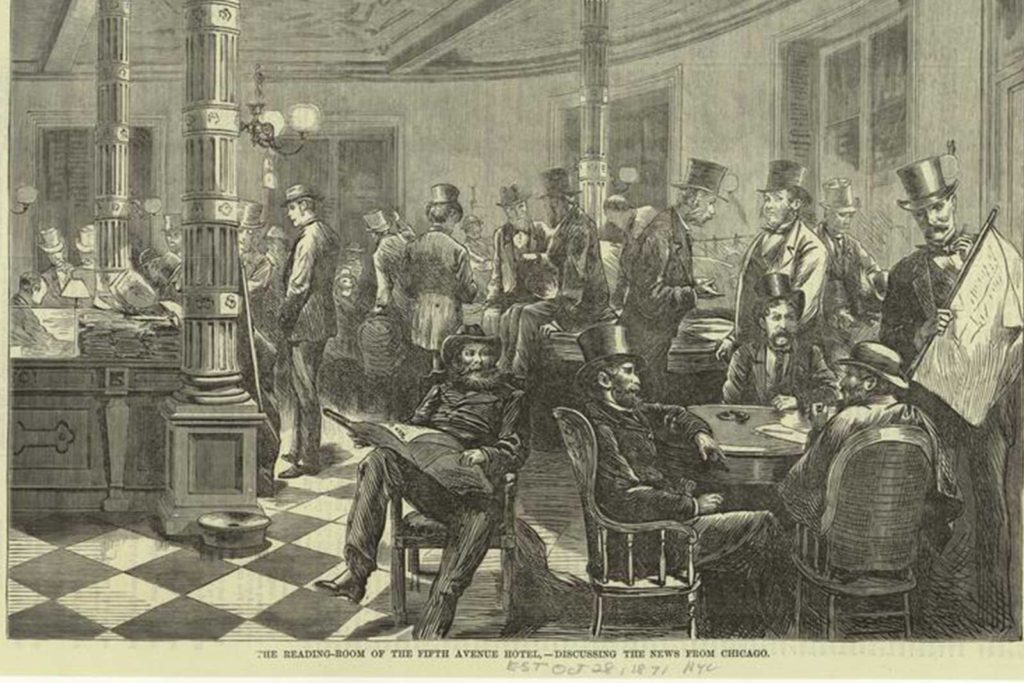

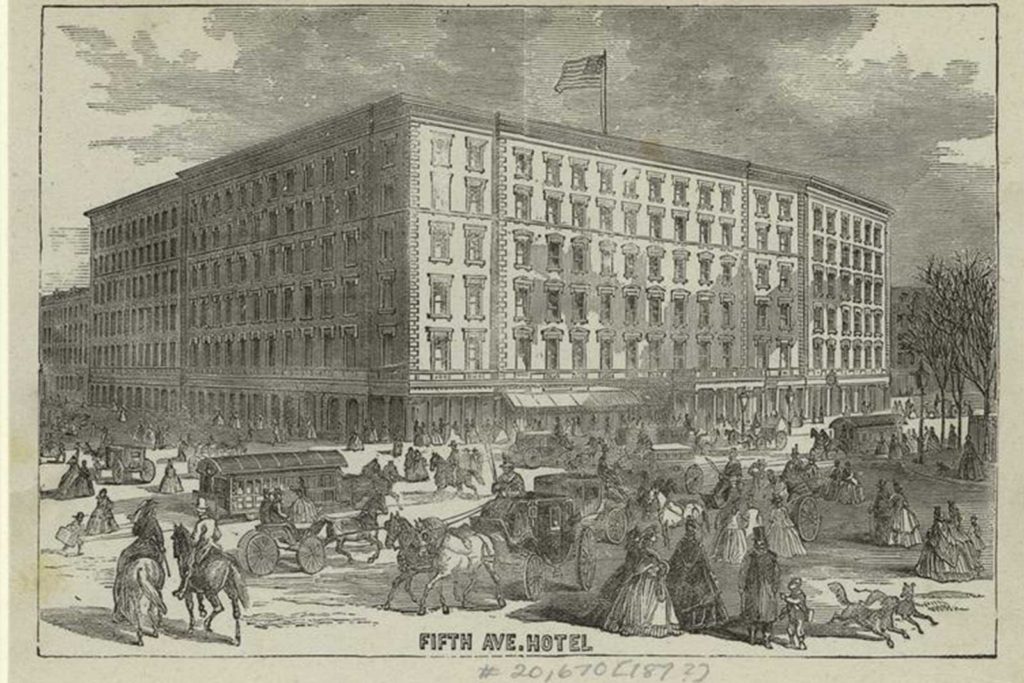

He rented a room at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, which he used until he left the country three days later. There are not many details of what he observed and saw in New York. In a letter to Ponce, he made an errant comment of visiting George Washington’s memorial. In another letter, he described the city to a friend as a place where ‘everything is new’. This is likely in comparison to Europe and even the Philippines, where the buildings were aged and antique, and made of other materials.

Rizal left the United States on May 16, 1888. He boarded a large steamer ship called the City of Rome, bound for Liverpool, England. As the steamer left the New York Harbor, he stood in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty on Bedloe Island.

Sources:

Zaide, G. F. (1999). Jose rizal: life, works and writings of a genius, writer, scientist and national hero. All-Nations Publishing Company.

Life and Travels of Rizal (2014). Retrieved from: https://travels-of-rizal.weebly.com/blog/life-and-travels-of-jose-rizal