What makes for a marker of identity? A marker of identity is a symbol, an object, or a set of activities that invoke a sense of belonging to a specific group or community. The Philippines is made up of roughly 7,000 islands and is home to over a hundred ethnolinguistic groups with their own distinct cultural identities. While these distinctions are important, how is a nation to function cohesively if they do not identify as a whole? To this problem the proposed solution was a series of national symbols.

In the Philippines, the social studies curriculum in elementary schools always consists of a unit or chapter dedicated to national symbols. Dr. Jose Rizal is the national hero. The national fruit is the mango. The national flower is the sampaguita. The critically endangered Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) is the national bird and the national animal is the tamed water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis, or Bubalus carabanesis). The pearl is the national gem—as the country is known as The Pearl of the Orient Sea.

While not all these national symbols have been legally recognized, these symbols are imparted to each generation of students, as an effort to overcome the ethnolinguistic divide and offer a more collective identity of the “Pilipino.” The Tinikling is widely considered as a national dance—if not the national dance—of the Philippines. The reason for this two-fold.

The first reason is likely due to most other famous Filipino dances being heavy with Spanish influence. The polkabal combines the polka with the waltz, the Surtido Cebuano is square dance from France. The carinosa is a fan and handkerchief dance mimicking European-style courtship in the eighteenth century. The tinikling has very little Spanish influence.

The tinikling’s place of origin is universally acknowledged by research. Tinikling originated from the Visayan province and island of Leyte. Its place in history, and the origin of the dance itself has many versions, and it is a point of debate for many. Some say that tinikling began as a part of a pre-Hispanic ritual curing ceremony.

Others suggest that tinikling sprang from a form of punishment the Spanish colonizers dealt the natives who refused to work in the rice fields by the colonizers. When the Spanish conquered most of the archipelago which would one day be the Philippines, they also took possession over much of the lowland plains ideal for agriculture and converted them into haciendas. A hacienda was a farm or plantation for cash crops such as rice, sugar, and tobacco that fueled the galleon trade which the Spanish used to connect their empire. The colonial government utilized the multitude of forcefully converted and subjugated natives to till and toil in the fields to produce crops for the galleon trade.

As a punishment to those who worked too slowly for their master’s liking, or those who tried to escape tilling the fields, the worker had to stand between two bamboo poles. These poles were clapped together to beat the worker’s feet. To escape their punishment, the worker jumped around the poles. Some believe that over time, this punishment evolved into the artistic and challenging dance known today.

The folkloric tale regarding its origin attributes the dance’s movement to that of the tikling bird. The tikling belongs to a number of rail species: the slaty-breasted rail (Gallirallus striatus), the barred rail (Gallirallus torquatus), and the buff-banded rail (Gallirallus philippensis). It is said that the dance imitates the movement of this long-legged bird as it dodges bamboo traps set by Filipino rice farmers.

The second reason for choosing tinikling as the national dance is that while it had its origins in the Visayas region, the components and movements of the dance had spread widely throughout the islands, each region imbued the tiniling with their own permutations and versions. One example of a famous variation of the tinikling is the sinkil.

Sinkil is a bamboo and fan-type dance of the Muslim groups in southern Philippines. According to Maranaw legend, sinkil mimics and narrates the story of a Princess Gandingan, who walked through the forest avoiding landing on trees and rocks which had fallen after the diwata or nature spirits, caused an earthquake. Both sinkil and tinikling are performances consisting of dancers nimbly skipping and dodging bamboo poles clapped together.

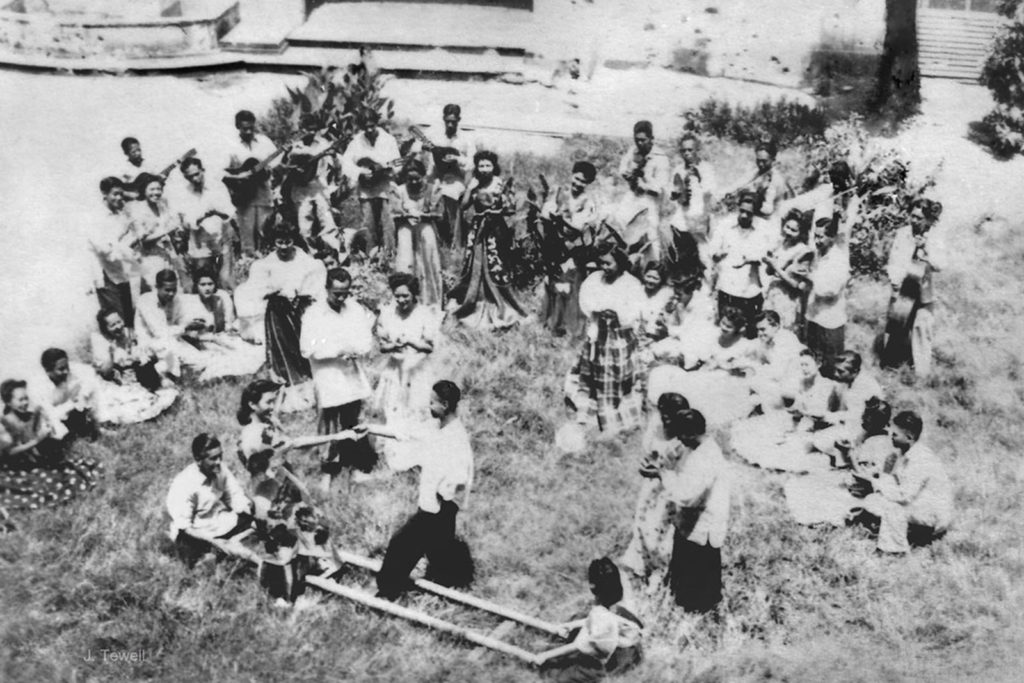

Among the many variations and styles, the basics of the performance involve at least three people. Traditional performances require an equal ratio of male to female performers. Female dancers usually wear a patadyong, a checkered loose skirt worn with a thin-fibered blouse. If not a patadyong, a colorful dress with arched sleeves called a balintawak is worn. For males they wear the barong tagalog, the country’s national attire for men. This is an embroidered formal shirt, usually of pineapple fibers, that is left untucked from a pair of red trousers.

Two performers, usually males, hold two parallel bamboo poles on the ground that measure 6-12 feet in length. The rhythm of movement consists of a 4/4-time signature. The poles are clapped against the ground for two counts, and on the third they are clapped against each other before the cycle is repeated. The third person—or, in most cases, a couple or trio—moves between the poles, dipping their bare feet between the poles when separated, and lifting them when the poles are clapped against each other.

A more advanced style uses a tic-tac-toe formation, with two poles across another set of two poles. The dancers, usually four or more, dance in a circular formation. And sometimes, if a group is skilled enough, or daring enough, the poles change position mid-dance, still keeping the beat of their clapping.

The timing of most tinikling performances start out slow, building a rhythm through a repetitive list of steps. Once rhythm is established for both performer and viewer, the accompanying music often speeds up. The increasing tempo prods the rhythm of the pole clapping to increase also which calls for more concentration and skill from the dancers to keep their feet from getting caught and crushed by the clapping bamboo poles.

While daunting, in recent years the dance has found its way out of specialized performances for events to Physical Education curriculums both within the Philippines and into schools abroad. This is because the dance teaches rhythm, speed, balance, and builds stamina.

Tinikling is a complicated and intricate dance, and that is not only in acknowledgement of its movements. As an identity marker, it allows those away from the Philippines to feel as a part of this greater identity through participation. It is not surprising that those outside the country seem to have a greater love for the dance than those living in the Philippines.

The fascinating thing about this phenomenon is how it is claimed by both Filipinos who have migrated to other countries, and the offspring of immigrants who have never set foot on Filipino soil. Physical education projects aside, most performances of tinikling outside the Philippinesoccur as demonstrations of Filipino identity. Many performances occur at cultural festivals or events in other countries where there is a significant population of Filipinos. By now it is safe to surmise that many have come to generally equate tinikling with beingFilipino.

And with this purpose, it is also true that tinikling has not remained stagnant in its traditional styles. There are dance groups that set their performance to pop and hip-hop music. The choreography is likewise revised to add modern dance movements and sometimes acrobatic tricks. Other modified versions increase the number of poles, pole placement, and dancers. If being a component of an identity has made tinikling relevant, innovation has kept it alive.

Sources:

Horowitz, G. (2009) International Games: Building Skills Through Multicultural Play. Human Kinetics. pp. 74.

Lane, C., & Langhout, S. (1998). Multicultural Folk Dance Guide (Vol. 1). Human Kinetics. pp. 27-33

Lewis, L. (2012). The Philippine “Hip Hop Stick Dance”. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 83(1), 17-32.

Lopez, L. (2006) A Handbook of Philippine Folklore. University of the Philippines Press. pp. 459-462.

“Researchers probe possible origin of “tinikling folkdance in Leyte.” (2006) Philippine Information Agency. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

“Tinikling Revolution” (2008). BrownNationCulture.com. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

Valdeavilla, R. (2018). Tinikling: The National Dance of The Philippines with Bamboo Poles. Theculturetrip.com. The Culture Trip Ltd.

Virtue, J. (2013) Tinikling. USC Folklore Archives. Retrieved 19 May 2021.