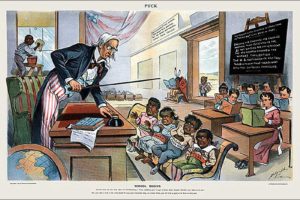

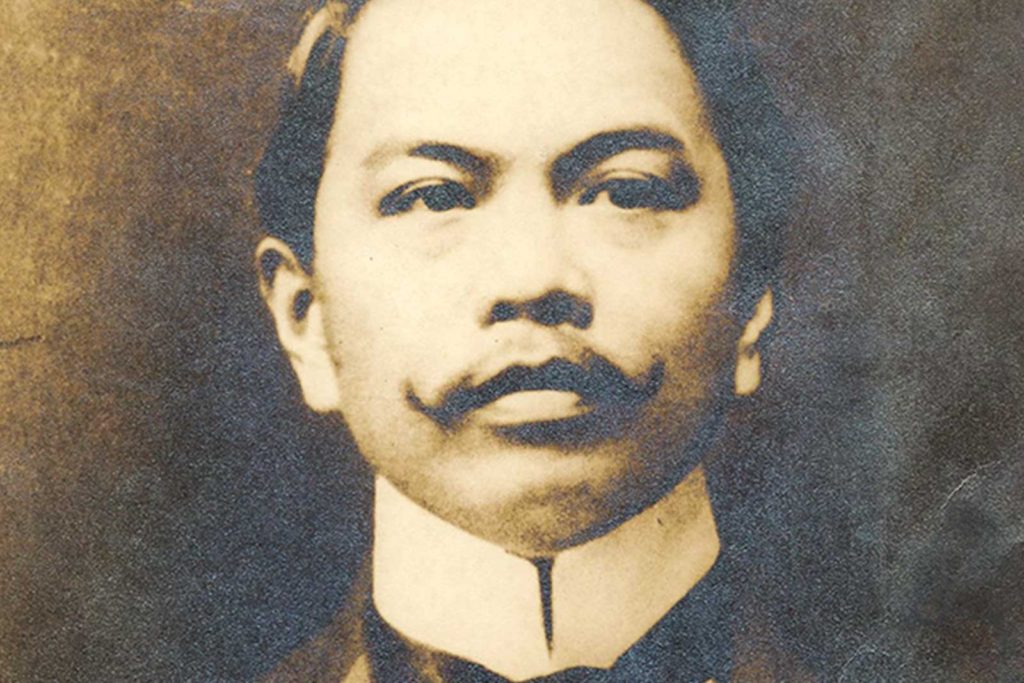

Juan Luna is considered a hero because his talent proved that the indio was not as savage or ignorant as the Spanish colonial authorities assumed and believed the indios to be. Luna’s life and work proved that by the late 1800s, the indios had reached a level of wealth, education, and influence that they had eclipsed the creoles (the full-blooded Spaniards who were born in the Philippine islands and resided there) and the peninsulares (the full-blooded Spaniards who were born in Spain but resided in the islands).

Juan Luna was born on October 23, 1857 in Badoc, Ilocos Norte. His family was part of the rising principalia class of indios—indios were natives of the islands who managed to rise up the socioeconomic ladder even with the oppressive colonial set-up. They became influential that some of them had been appointed to local political positions.

The indio principalia suffered the same injustices as the Chinese and the mestizos. Mestizos were children of Chinese and Spaniards who intermarried with indios. The wealth of the principalia, the Chinese and the mestizos allowed them to have their sons educated beyond the basic grammar education provided by the village or town priest. They sent their sons to learn a trade or profession in the colleges and universities in Manila. These well-to-do, educated and urbanized indios and mestizos were also referred to as ilustrados (the enlightened ones) for their enlightened ideas and liberal turn of mind.

Luna studied in the Ateneo Municipal de Manila (just like Rizal) where he excelled in the arts, particularly in painting and drawing. However, because he did not yet realize that he could make living off his art, he also studied to become a sailor while taking art lessons from a private tutor. He obtained his pilot’s license when he was only 17. Through his mentor’s encouragement, Luna took courses at the Academia de Dibujo y Pintura. He did not finish his course in art school as he disagreed with his teachers. One teacher saw his potential and advised him to study in Madrid.

Fortunately, Luna’s family was wealthy enough to afford sending Juan Luna and his brother Manuel to Madrid where Juan Luna enrolled in the Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. But, again, Luna did not feel he was learning much from school and decided instead to apprentice himself to a master. The master took Luna to Rome to help fulfill a painting commission. There, Luna was exposed to classical art in Rome.

In 1881, Luna had finished a painting he entitled La Muerte de Cleopatra. He entered it in the Exposicion Nacional de Bellas Artes where it garnered a silver medal. In 1884, his work Spoliarium won four gold medals at the same Exposicion Nacional de Bellas Artes in Madrid but the committee refused to give Luna the top prize because he was an indio. His work won all the four gold medals at stake but he was not recognized as the winner.

The Exposicion’s snub of Luna earned for Luna the sympathy of Spain’s King Alfonso XII who appreciated Luna’s talent. Luna was later commissioned by the Spanish Senate to do a painting and he submitted to them his work La Batalla de Lepanto. In 1887, Luna entered that painting and another entitled La Rendicion de Granada which also won in the exhibition.

Luna had made a name for himself that even the Spanish colonial government in the Philippines commissioned a painting that depicted Philippine history (as viewed from the Spanish perspective, of course). Luna produced El Pacto de Sangre (The Blood Compact) which showed the blood compact between Datu Sikatuna and Miguel Lopez de Legaspi.

Later, Luna moved from Spain to Paris where he set up a studio. In Paris, he was in the company of another famous Filipino exile, Jose Rizal. Together with other Filipino students in Paris, they formed a colony of artists and writers who sought to expose the oppression of the indio from the Spanish colonial authorities through their art.

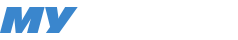

Luna was influenced by the Impressionist movement which was then all a rage in Paris. Luna painted street scenes and workers. His output while in Paris had a distinct theme from the classical and historical themes of his paintings while he was in Madrid.

While living in Paris, Juan Luna also met and married Maria Pardo de Tavera who belonged to a mestizo family from the Philippines. Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, the uncle of Maria was the lawyer of the three martyred priests, Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, Jacinto Zamora who were found guilty of conspiring in the Cavite Mutiny of 1872. After the Cavite Mutiny and the execution of the three priests, Joaquin Pardo de Tavera was exiled to the Marianas Islands. Maria’s mother was widowed by then and she brought her whole family and followed her brother Joaquin. The Paris home of the Pardo de Tavera family was where expatriates in Paris like Luna and Rizal converged and discussed their ideas of freedom and social justice, reform and revolution.

Juan Luna’s time in Paris was marked by a prolific production of art but was also marked by marital problems. Luna was consumed with jealousy and he often accused his wife of infidelity. In 1892, Luna shot his wife and mother-in-law to death and wounded his brother-in-law. He was charged with murder by the Paris police but was subsequently found not guilty by reason of insanity. His lawyer defended him by convincing the judge that Luna was an indio and was thus savage and lacked the refinement of temper that civilized European people possessed.

A lot of scholars have pointed out the irony that Luna, who had striven through art to prove the equality of the indio with the (White) colonizing powers was saved from prison by pleading that he was not at all equal in civilization to the (White) colonizing powers.

Luna returned home to the Philippines in 1894 and he did paintings while back at home. However, when the Philippine Revolution broke out in August 1896, Juan Luna and his younger brother Antonio were arrested and imprisoned at the Fort Santiago for their alleged complicity in the Revolution. While in prison, Juan painted portraits of his family members while his friends and family sought a royal pardon for the brothers. After his pardon and release, Juan Luna left the Philippines bound for Europe once more.

In 1898, the Philippine Revolutionary government (of Emilio Aguinaldo) entrusted to Luna the job of seeking recognition from the French of the newly formed Republica Filipina. In 1989, Luna became a member of the delegation sent to Washington, D.C. to press the US Senate to recognize the Aguinaldo Government as the Philippine Government. However, his stay in the US was cut short when his brother, General Antonio Luna, was assassinated by the Kawit Batallion.

On his way back to the Philippines, when the steamer was in Hong Kong, Luna suffered and died of a heart attack. He was buried in Hong Kong and his remains were exhumed in 1920 and placed in a crypt at the San Agustin Church. Five years later, at the St. Louis World Fair, Luna’s last major work Peuple et Rois was entered posthumously and won best entry. Even after his death, Luna still tried to show the world that the indio ought to be treated equal to other races because the indio is equally endowed with talent and humanity.

Sources:

Diokno, Maria Serena I., and Villegas, Ramon N. (eds.) Life in the Colony. Volume 4 of Kasaysayan: A History of the Filipino People. Asia Publishing Company, Ltd., 1998.

Guerrero, Milagros C. and Schumacher, John N. (eds.) Reform and Revolution. Volume 5 of Kasaysayan: A History of the Filipino People. Asia Publishing Company, Ltd., 1998.

“Juan Luna.” Wikipedia.com. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Luna