What we call “history” is the carefully constructed story of a people or nation through the ages. Each name and event in the textbooks are chosen to shed light on the becoming of a nation. The causes and persons that do not fit the desired narrative are glossed over or repurposed. If ever they are mentioned, they are often tacked on as afterthought, or additional information. But while some heroes may not have fit the mold of the desired narrative of the history of their people, their stories do serve a purpose. One such hero is Gabriela Silang.

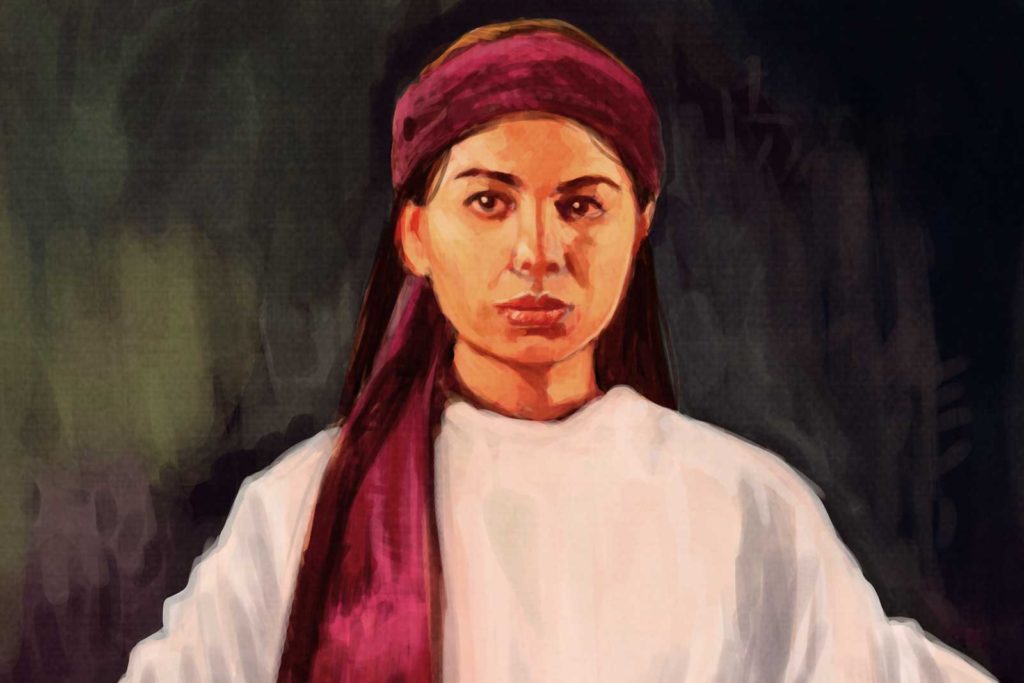

The woman whom history would later herald as henerala (woman-general), the Great Ilocano Heroine, was of plebian heritage. Maria Josefa Gabriela Carino, who would later be known simply as Gabriela Silang, was born on March 19, 1731 in Santa, Ilocos Sur. She was born to an Ilocano peasant father, and an Itneg mother. The Itneg were a pagan ethnolinguistic group dwelling in the Cordillera mountain ranges that dominate most of northern Luzon.

At the time Gabriela was born, the town of Santa and the rest of the Ilocos region had been under Spanish rule for at least 200 years. The town was a suburb of Vigan, the principal maritime town of northern Philippines, and both Vigan and Santa were colonial outposts at the mouth of the Abra River. This river was, in turn, the gateway to the Cordilleras. The Cordilleras are the highland mountain ranges that were home to tribes that remained pagan despite the steadfast conversion of the lowlands to Spanish Catholicism.

The cross-cultural marriage of Gabriela’s parents compounded the discrimination that the illustrado class exhibited towards the indios who were mostly peasant farmers, and the pagan highlanders. The illustrado made up the principalia, the class of native elites who worked for the Spaniards as administrators and tax collectors, and who wielded incredible power that was often abused.

Gabriela escaped the assassination attempt. But fearing retaliation, the alcalde mayor of Cagayan initiated a pursuit of the remaining rebels. Rallying troops, Gabriela withdrew to her mother’s town in Pidigan, Abra, in search for support among the local warriors.

The comun, or annual tribute, was a heavy tax burden imposed on farmers. And the principalia did not hesitate to collect taxes over and above that which was decreed by the Spaniards. The system of colonial governance and society with a wealthy and influential principalia class ensured that the indio would always be underfoot, subservient. The subjugation of the indios had as much to do with their ethnicity as well as their economic situation.

Perhaps it was the maltreatments and disadvantages suffered by the indios that spurred Gabriela’s father to engage her to a rich man. She was married when she was twenty years old, but her husband died shortly after. Now a reasonably wealthy widow, she attracted many suitors. She took for her second husband an educated man from Vigan named Diego Silang. He, unlike her, was of the principalia. But unlike many in his class, Diego opposed the many unscrupulous practices of his class, particularly, of the alcalde mayor, Antonio Zabala.

In the middle of the short marriage of Gabriela Silang to Diego Silang, the Seven Years’ War began in Europe. Spain allied with France against Britain. And the repercussions of the war in Europe reached even the Philippines. In 1762, British warships sailed from Indian ports to oust the Spaniards from their outpost in Manila.

The British takeover of Manila itself, the seat of the colonial government, was quickly ended, but elsewhere across the archipelago, the Spaniards continued to resist British incursions into their colony. With their armies and resources taken up by the war in Europe, the British employed a different tactic in the Philippines. The East India Company Provisional Government of May 1763 drew up a manifesto. The manifesto guaranteed colonized natives of the Philippines rights that the Spanish colonial government had deprived them. The British baited the residents of the Philippines with promises of equal treatment, possession of their properties, freedom to practice religion, and freedom from all taxes and oppression.

It was likely a pretty lie. If the Seven Years’ War had taken a different turn, the Philippines might have become a British colony, and eventually it would have become part of the British commonwealth. But the economic situation for peasant farmers and indios would have been the same across the archipelago under the British crown as it was under the Spanish crown.

Regardless, many were tempted by the promise of a greater form of independence from what they had previously known. Among them was Gabriela’s second husband, Diego who threw in his lot with the British. Together with Gabriela, he organized an armed force which defeated the Spaniards at the town of Cabugao. Soon after this, the Spaniards were removed from Vigan.

On December 14, 1763, Diego proclaimed the independence of the Ilocos region, and established a government of the people. To this, Governor Dawsonne Drake titled Diego as Don Diego Silang, and sanctioned him as the rightful head of the Ilocos government.

The changes the Silang’s instituted overturned the practices that allowed the principalia to enrich themselves at the expense of their poorer countrymen. The feudal practice of corvee, or unpaid labor, and the paying of tribute were removed. Instead, the principales were required to pay for the maintenance and upkeep of their government. The principales were allowed their normal lives, in exchange for their non-aggression.

Gabriela collaborated with her husband, she was his closest ally and confidant as they incited rebellion. Together set out to overturn the social pyramid. Their efforts began among the townsfolk, but they had hoped to reach the inlands and uplands. All this was done despite the fact that Gabriela, through her marriage to Diego, was now firmly a member of the principalia herself.

Of course, the church functionaries and elites were not pleased with these changes. Ilocos was an important region in the north, and Vigan a most important port. Bishop Bernardo Ustariz proclaimed himself provincial head, and excommunicated Diego Silang in the latter part of May 1973. Furthermore, he hired Miguel Vicos and Pedro Becbec to assassinate not only Diego but also Gabriela.

The attempt was only half-finished. Diego was shot. Convinced that the shot had not killed him, several elites of the town of Santa stabbed the corpse. Becbec was rewarded for his efforts with the title and responsibilities of justicia mayor of Abra.

Gabriela escaped the assassination attempt. But fearing retaliation, the alcalde mayor of Cagayan initiated a pursuit of the remaining rebels. Rallying troops, Gabriela withdrew to her mother’s town in Pidigan, Abra, in search for support among the local warriors.

Gabriela organized a force that launched a surprise attack against Becbec and his forces in Santa. They fled. Gabriela then turned her forces to Cabugao, where she established a fortress for the revolutionary army.

She was successful for a time, until the Spaniards organized a force some 6,000 strong for a counterattack. On the 11th of July, 1763, the Spaniards retook Vigan. Recognizing the importance of the town, Gabriela launched her own attack. She was unsuccessful. Arrows, and bullets, and cannons came at her army of 2,000 warriors. Terrified, those who survived retreated back to their camp in Abra.

A small force led by Manuel Arza y Urrutia followed in pursuit. He offered rewards to the tribes of the Cordilleras for information on Gabriela’s camp. Before long, Gabriela and her followers were captured.

Ninety or so of loyal silanistas, Silang loyalists, were hanged along the Ilocos Sur coastline. Hundreds more of suspected followers were flogged and tortured. And Gabriela was made to watch it all before she herself was executed on September 20, 1763.

It is not a surprise that Gabriela Silang’s story is untold for it is a story rooted in class oppression as much as it is rooted in colonial oppression. Most people even in the Philippines would only know that Gabriela Silang was the wife of Diego Silang—a gross underestimation of not only her efforts but the efforts of all the little rebellions that occurred before the one at the end of the 19th century.

The rebellion of Diego and of Gabriela Silang is not so well known to people because their rebellion, along with other rebellions against the Spanish colonial government was a local rebellion—the Silang rebellion only comprehended the province of Ilocos Sur. They revolted not only against the Spanish colonial overlords but also against the local principalia class of Filipinos.

While story of Gabriela Silang does not fit into the smoothly linear progression of events that history requires many students to learn, it does teach a lesson. Three hundred years of colonial rule had hammered the indio into submission, had taught them that their place was below all even within their own homeland. Silang’s rebellion may not have been the grand climax of the tale, but it was a chapter that proved a point. It was possible to rebel. The Filipino was capable of fighting, rebelling, of governing themselves.

Sources:

Ancheta, Herminia M., and Michaela Gonzales. Filipino Women in Nation Building. Quezon City: Phoenix, 1984, pp. 248-249.

Pagador, Flaviano R. “Maria Josefa Gabriela Silang, the Great Ilocano Heroine,” in Ilocos Review. Vol. 2, no. 2, 1970.

Routledge, David. Diego Silang and the Origins of Philippine Nationalism. Quezon City: Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, 1979.

“Silang, Gabriela (1731-1763).” Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Retrieved: May 06, 2021.