It’s difficult to say for certain that the early pre-colonial Pilipinos had weapons and what those weapons were. For one, if we say they had weapons, it would imply that they were warlike peoples and it would also imply that they had knowledge of metallurgy or metal working. Without proof that pre-colonial Filipinos had mastered metallurgical craft, then whatever weapons they may have used may have been weapons they had bought or traded for from sea merchants or they may just have obtained those weapons by pure chance.

For a long time, the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands have been thought of as “savage” and “backward” and thus, they were not thought to have any knowledge of metal working because this craft involves labor-intensive activities such as sourcing metals (knowing where metals can be found), mining them (or removing and separating them from the rocks), smelting and melting the metal to purify them before they can be forged and steeled.

Of course, metallurgy is an art and a craft associated with “civilization” and 19th century historians did not think that native inhabitants of the islands had any “civilization” to speak of. Some have maintained that metallurgy was too sophisticated a craft for the primitive inhabitants of these islands. Some have even posited that any weapons found by archeologists in the Philippines may not have been crafted in the islands, thus, those weapons could not in any way be rightly called “traditional” weapons but weapons that had been “borrowed” from other cultures. Indeed, a lot of the weapons found through archeological digs in the Philippines bear some similarities with weapons from other nearby cultures.

Iron tools as archeological finds

Archeological finds in recent decades have supported the idea that the art of metallurgy in the islands was a thriving occupation. Archeologists have found a socketed blade in Palawan as well as copper and bronze socketed axes, spearheads, arrowheads, knives and harpoons. But some argued that these may not be weapons but tools for hunting, for felling trees to make into canoes or to make shelters.

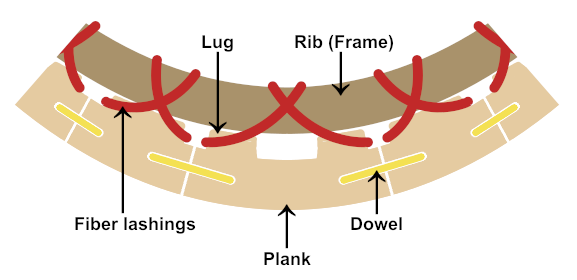

The Butuan boat

The discovery of the Butuan Boat shows that Filipinos felled trees for wood, hewed planks from the trunks of the trees, shaped them and assembled them using bark from saplings processed into rope and lashings. Interestingly, the boards and planks were attached to each other using wooden pegs. At first glance, a boat made with wooden pegs cannot directly point to a craft of metallurgy—the boat didn’t even have any iron nails on it.

But this is precisely the point: pegs have to be shaped and smoothed with precision; the holes to put the pegs in needed to have been gouged out of the wood and this type of precision carpentry and shipbuilding could have only been accomplished using fine and sharp metal tools.

Of course, some looked down upon the Butuan boat saying that the lack of metal nails only proves that Filipino shipbuilding skills were crude at best. However, consider that wood expands and contracts depending on the heat and moisture it is exposed to. Wooden pegs on boats would swell inside the holes and keep the boat’s integrity while it is at sea, whereas iron nails would have rusted and corroded. The decision to use wooden pegs instead of nails may not imply the lack of iron nails but it may imply instead that they had found wooden pegs to be more efficient and durable for the task than iron nails.

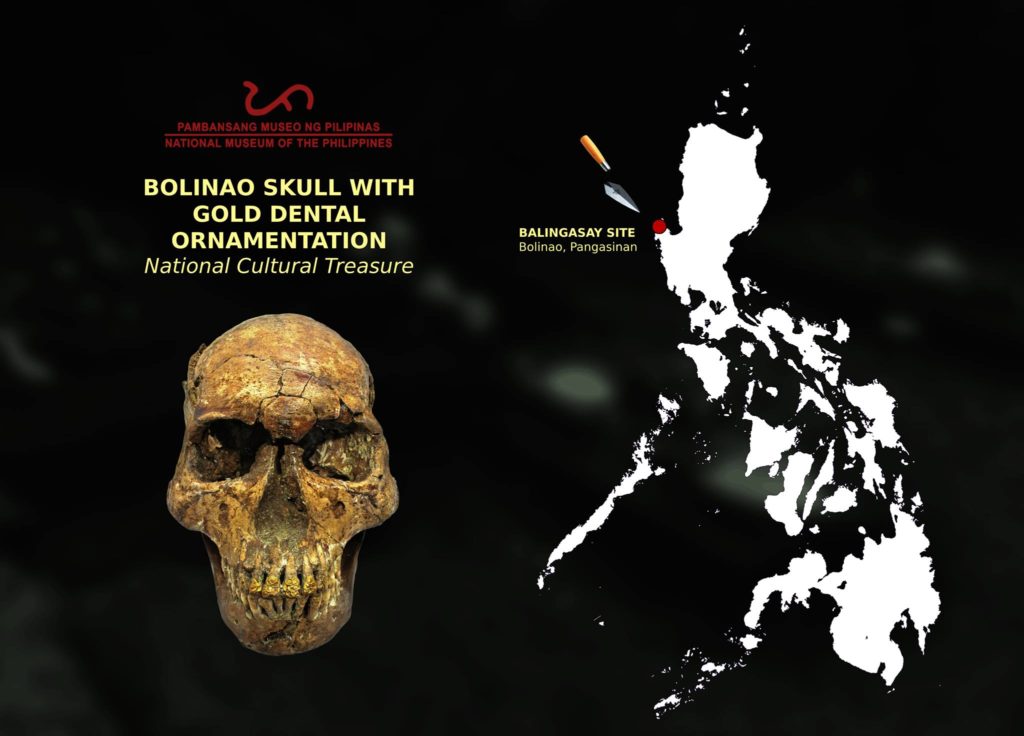

The Bolinao Skull

But beyond metal weapons or tools, archeological evidence such as the Bolinao Skull shows that Filipinos embedded scale-like sheets of gold on the teeth as status symbols for wealth and bravery. The fashioning of jewelry from gold is evidence of a fine knowledge of metallurgy among Filipinos. Consider that before gold can be fashioned into jewelry, it needs to be panned from shallow river beds or broken off from rocks first. The rocks have to be crushed and all the gold nuggets would have to be smelted or purified. More importantly, pure gold is a pliable metal—to be made into jewelry, it has to mixed with other metals such as bronze or copper to make gold more stable. And then, it will have to be pounded thin and shaped.

Jewelry and weapons in the Boxer Codex

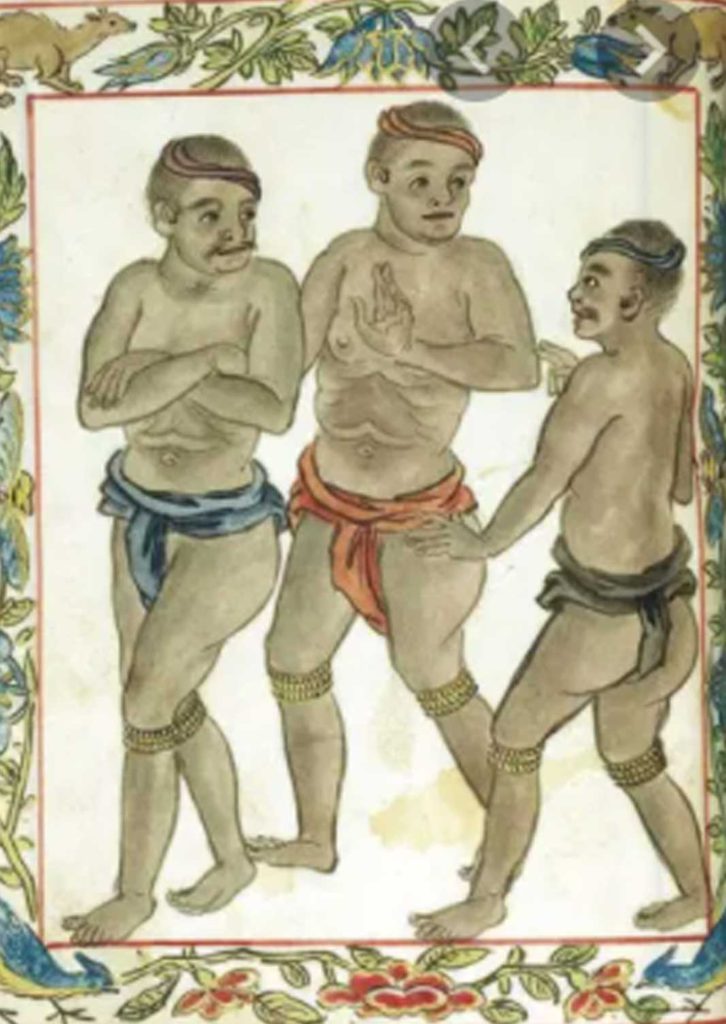

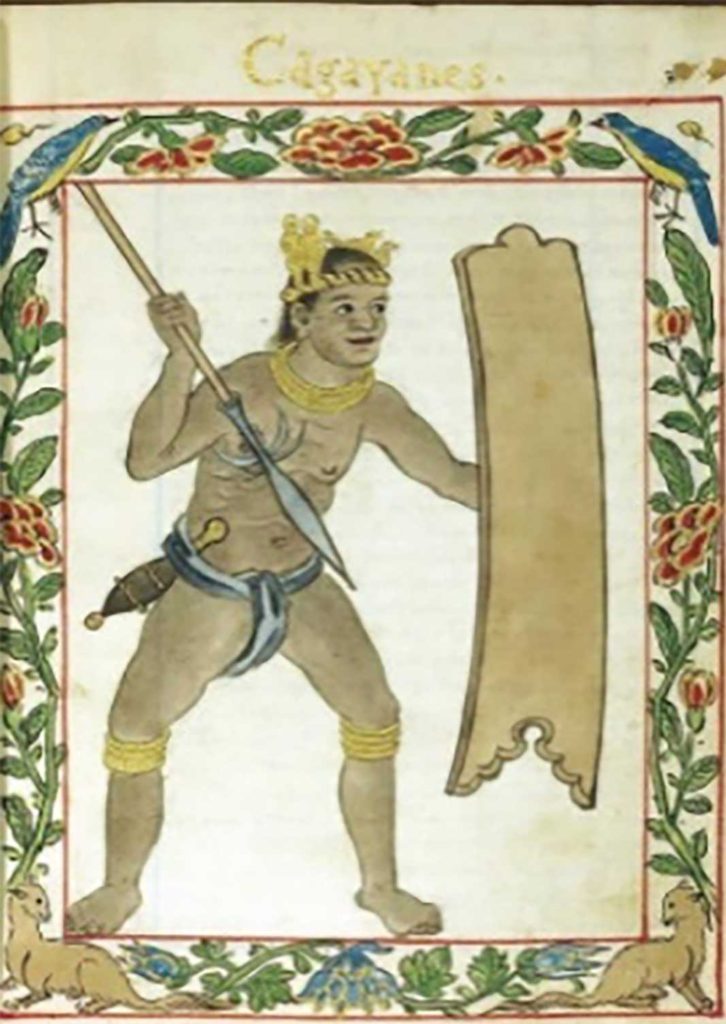

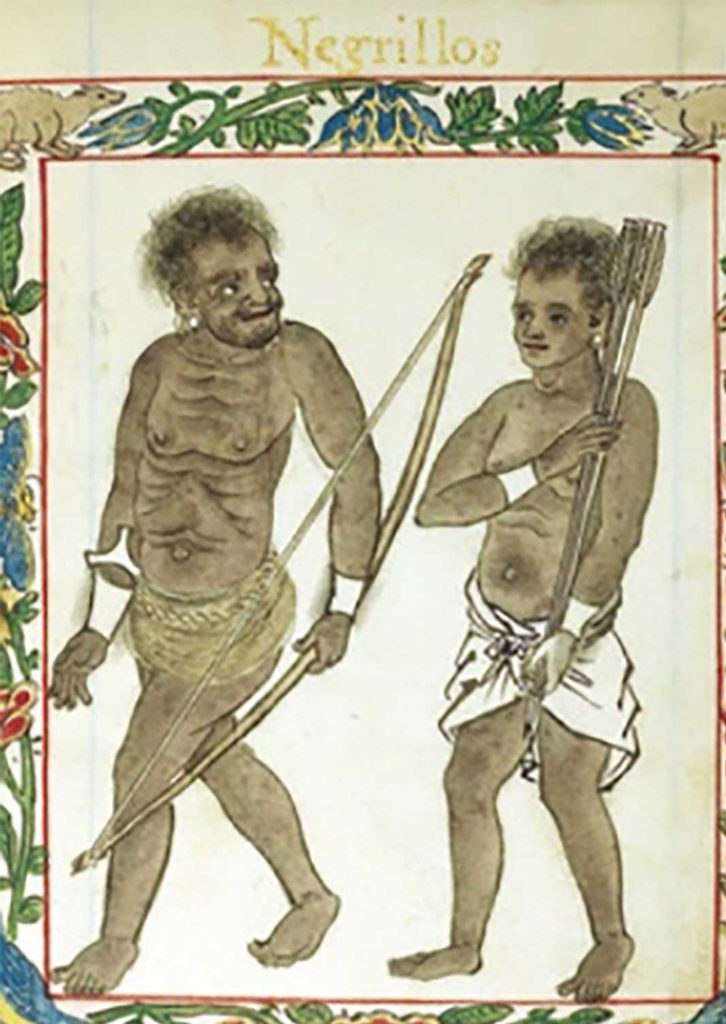

Perhaps, more important than archeological finds that only indirectly point to the existence of metallurgy in the Philippines is a pictorial evidence that the earliest Pilipinos used jewelry and bladed metal weapons in their every day life. For this, we can turn to the Manila Manuscript that is also known as the Boxer Codex.

The Boxer Codex is an illustrated book published in 1590. It contains illustrations made by a Spanish scribe that accompanied the conquistadores. The illustrations were of the inhabitants of the Philippines at the time of the initial contact with the Spanish conquistadores. The art historian Charles Ralph Boxer discovered the Manila Manuscript in 1947 and it was named after him.

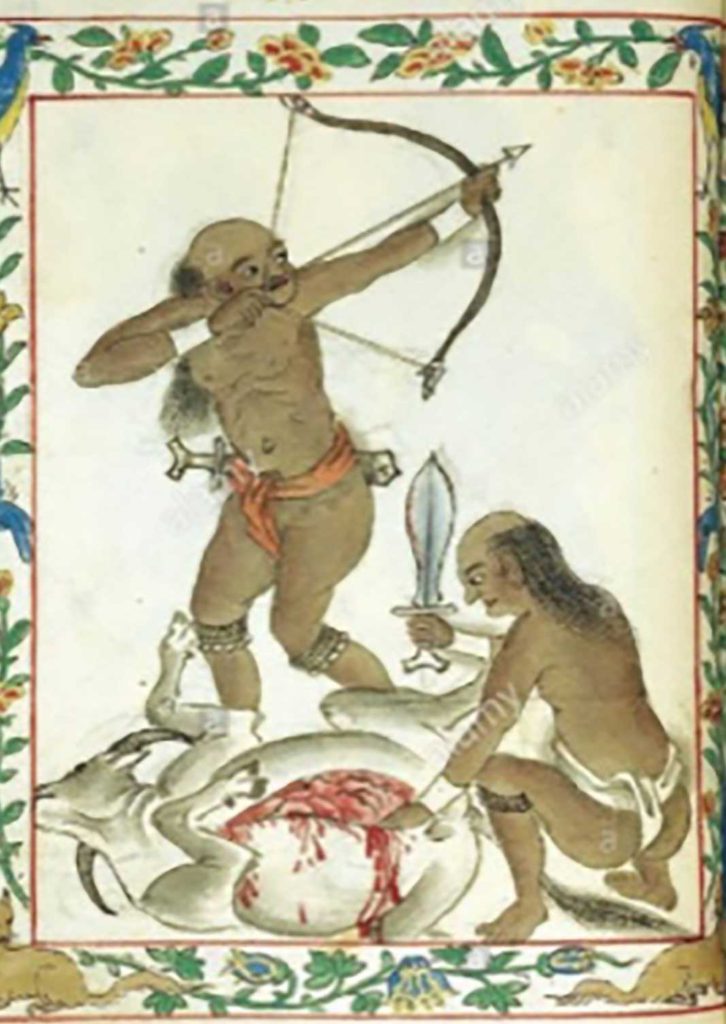

The Tagalog males of royal blood called kadatuhan who wore red colored clothes also had a sword at their side and they were also bedecked with gold. A male warrior carried a shield, a sibat or spear, with a long sword at his side. Another illustration of a warrior from Cagayan showed him carrying both a short leaf-shaped sword called a barung and a sibat. Another illustration of two Sambal warriors showed them carrying pana (bow and arrow) and a short dagger. Still another illustration of the same Sambal warriors showed one of them having shot an arrow through a deer and the other warrior slicing up the carcass with his barung.

The illustrations in the Boxer Codex showed alipin (slaves) who wore earrings and bracelets around the bottom of their knees—yes, gold was abundant that even the alipin had the right to adorn their bodies despite their low status in society. The upper classes of maginoo wore blue; the male had a sword at his side; and both the male and the female were bedecked with heavy gold chains around their necks, their wrists and below their knees.

From these illustrations, we can glean some insights: first, in pre-colonial Philippines, slaves were not allowed to carry weapons but they were allowed to adorn themselves with simple jewelry; second, blades were used as both weapons and tools; third, the type of bladed weapons used were also associated with one’s status or rank in the community.

Miguel Lopez de Legaspi came to the Philippine Islands on February 13, 1565 and from his diary he made mention of the natives of the islands as “hostile.” He noted that the warrior classes were divided into the sandigi (guards), kawal (knights or vassals of the datu), and tanods (keepers of the peace). This shows that there was a warrior culture among the inhabitants of the Philippines at around the time of the Spanish conquest. Indeed, the first Spaniard who had set foot on the islands, Ferdinand Magellan was hacked to death either by Lapu-Lapu himself or at his command and direction.

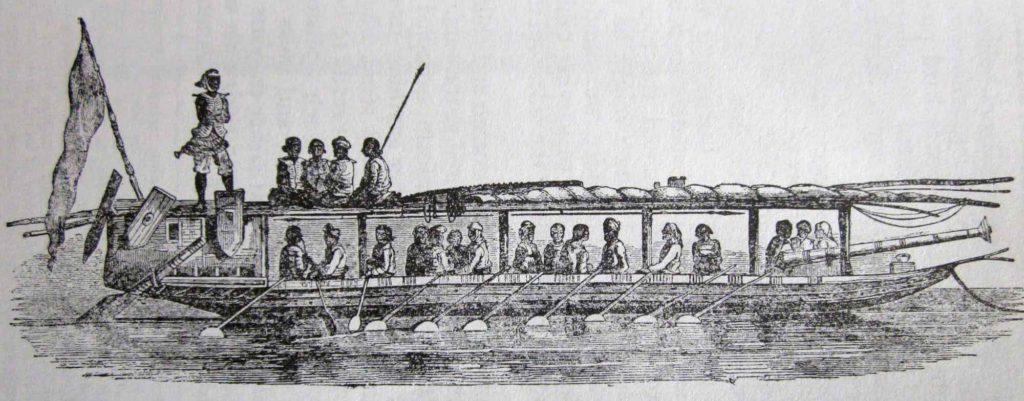

In 1571, when the Spaniards tried to penetrate into the environs of Mindanao, they were met with swift boats that had mounted brass long cannons called lantaka. A Filipino blacksmith named Panday Pira (1483-1576) was credited with having crafted and developed the lantaka. His craftsmanship was of such high quality and usefulness to the Spaniards that they commissioned Panday Pira to make lantakas to be mounted on the ramparts of the Spanish walled fortifications to discourage pirate raids along the coasts.

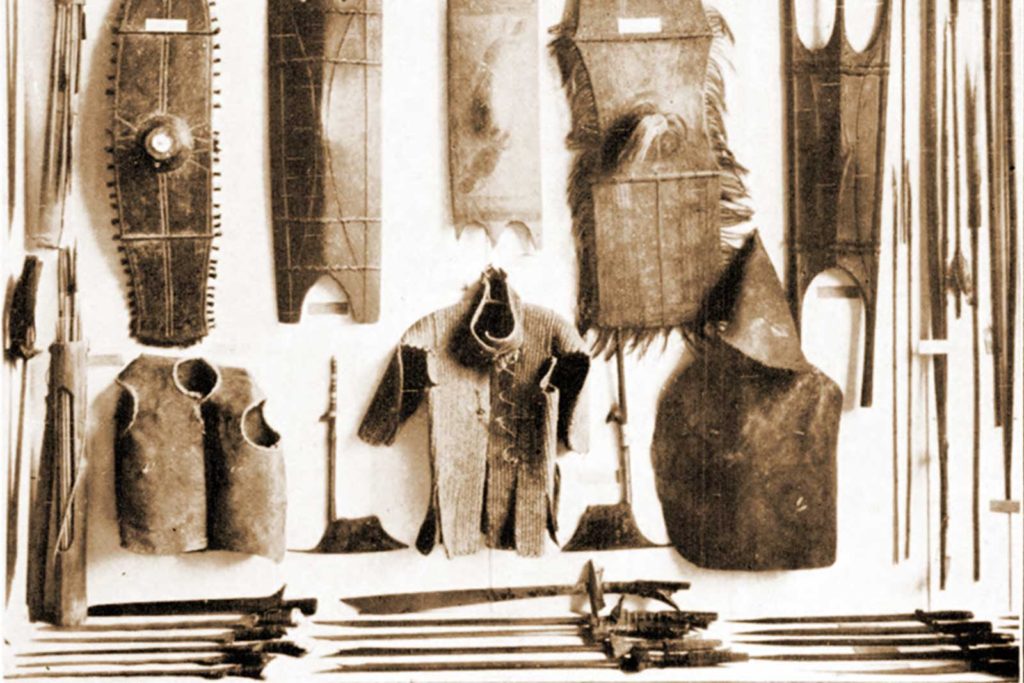

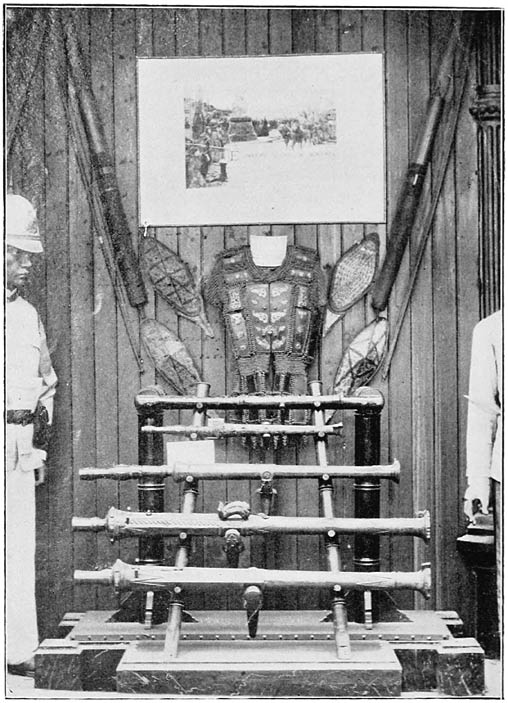

Moto Lantakas and Coat of Mail, Philippines, 1900

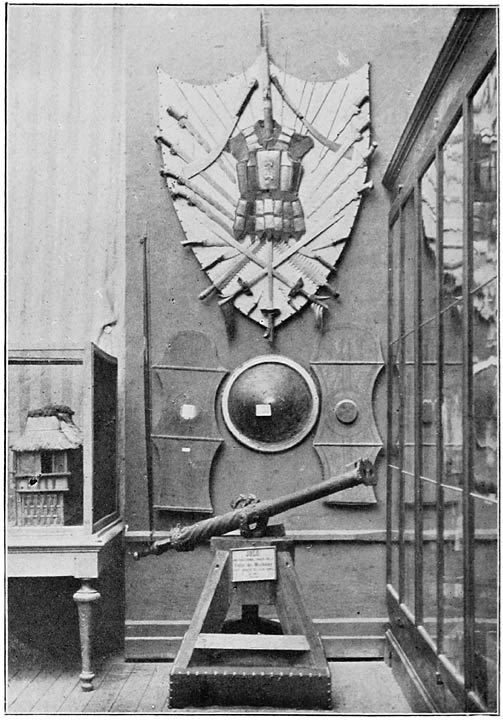

Double-barelled Lantaka of artistic design and Moro arms, Philippines, 1900

Lantaka Swivel Gun Display, Museum of the Filipino People, Rizal Park, Manila, Philippines

Lantakas

Nicola.gelmi, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

An Illanun war-boat; a lantaka can be seen of the prow. Drawing taken from the book of Frank Marryat Borneo and the Indian Archipelago (1848)

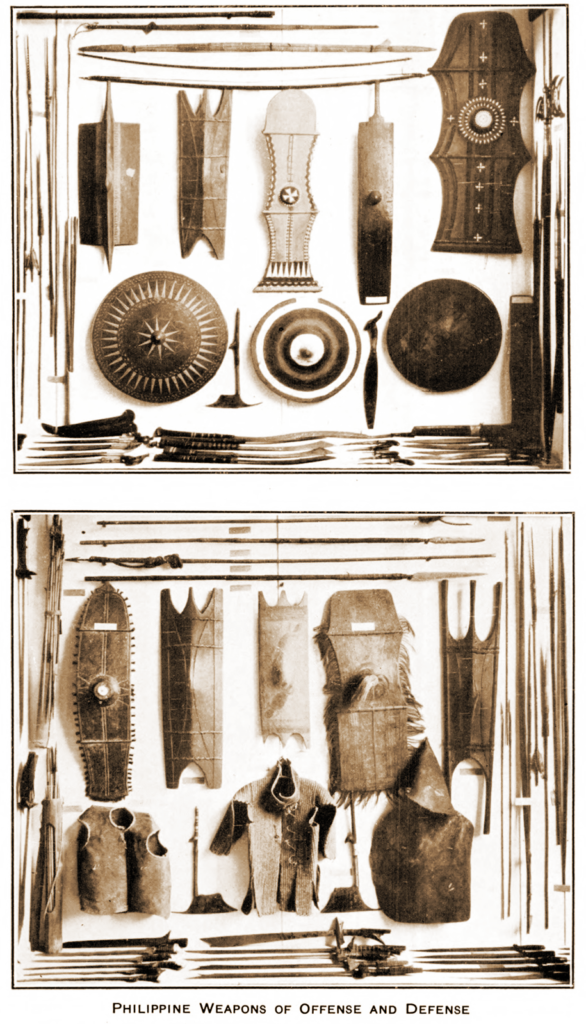

Legaspi noted that the native warriors used tactics such as raids and ambushes. Using these tactics associated with guerilla warfare techniques allowed the native inhabitants of Mindanao to repel the Spaniards and to keep themselves away from the oppression of colonization. The kris is one type of sword from Mindanao that distinguishes itself with the wavy pattern of its blade. It is said that the more waves the sword has, the more prestigious the owner was. This blade was used both as a weapon and as a ceremonial symbol.

While some would concede that perhaps the native Pilipinos may have had some skill in weapon- forging, their weapons were not intricately crafted and didn’t have much aesthetic value. But consider that the blades and swords were used both as tools and weapons, and the tactic of choice for waging war was through ambush and raids. This meant that blades and weapons were not always used for their ceremonial or ritual value.

It may mean, however, that the shape and length of the blade had to serve the purpose of both weapon and tool; it must be durable, sturdy, portable, and easily concealed. Indeed, archeological evidence shows that bladed weapons in the Philippines had a pointed end perhaps to pierce through bark armor of enemies. But they also had one or two sharp edges to hack through thick jungle foliage. The swords were not used for any fencing but to strike a hacking blow on an enemy or a rampaging wild boar. And the bladed weapons could not be too long for that would hinder a warrior from quietly and stealthily moving through a thick jungle to kill his prey.

For this reason, we have short swords called the balarao, the medium-length sword called the kampilan, the leaf-shaped sword called the barung, and the long thin sword called the bolo or itak. Warriors, however, also used tirador or slingshot, a sumpit or blowgun to fire poisoned-dipped darts, and a balisong or fan knife to stab enemies that they can get to. The Boxer Codex showed that warriors often carried an assortment of bladed weapons and while they may have had a long sword, they also had a punyal or a sundang dagger tucked into their waist. Some even carried a karambit, a small dagger in the shape of a claw meant for concealment in the hand and designed for a close-in kill or assassination.

So indispensable were bladed weapons as tools in the agricultural life of the pre-colonial Filipinos that the Spanish colonizers could not ban them altogether. Instead, the Spanish authorities mandated that indios wear bright colored pants (usually red) and a shirt made from thin sheer fibers so that the Spanish guardiya sibil would be able to tell at a distance if the indio was armed with a bladed tool/weapon.

Another weapon that posed as an everyday tool was the rattan pole. Rattan poles are slung over the shoulder and are used to suspend by rope two buckets to carry water or two baskets filled with grain or produce at either end. But if the peddler or merchant is beset by thieves or brigands, the carrying pole can be used much like a club or a sword. It can parry attacks and deal injurious blows on the head, the shoulder, the back or the chest and it can even break the knees of the attacker. These rattan poles are called kali or arnis depending on the area of the islands, in some places, the word arnis refers to the martial art that instructs on the use of the kali.

During the Spanish colonial era, when carrying a bladed weapon in towns would surely bring unfavorable attention or detention from the guwardiya sibil, Filipinos began to embed homemade long thin needle-like swords inside rattan poles for personal protection and also to carry out stealthy raids and attacks. These cached swords were called caborrata.

Everyday bladed tools such as the gulok and the panabas were often used to cut long grass or to weed and prune trees and shrubs in the country or farm. They could be used to slice snakes in two while in the jungle or slit the throat of a chicken for lunch at home. And yet, these tools were also used as weapons. When the Philippine Revolution broke out in 1896, Bonifacio and his men were armed with bolos and other bladed tools more suited to the work of farming and clearing jungles for farming.

This shows that ordinary everyday implements primarily used as tools were repurposed as weapons depending on necessity. On the one hand, this speaks of the unpreparedness of the Philippine Revolutionary forces to wage war against Spain. But on the other hand, it shows the resourcefulness of the revolutionaries—they used whatever they had on hand, and whatever was accessible, to wage the war for independence.

The inferiority of their weapons against the artillery and cannons of the Spaniards can only highlight the bravery, valiance, and skill of the revolutionaries as warriors. The shortness and thinness of the traditional blade design implied that these were intentionally used in stealth as they were almost always concealed. It also meant that warriors needed to have bravery to get close enough to an enemy without being detected, close enough to use a small blade to slit the enemy’s throat.

Sources:

Casal, Gabriel S., Dizon, Eusebio, Z., Ronquillo, Wilfredo P., and Salcedo, Cecilio G. The Earliest Filipinos. Vol. 2 of Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People. Asia Publishing Company Limited, 1998.

Barrows, David P. A History of the Philippines. World Book Company, 1914.

FilipiKnow. 17 Most Intense Archeological Discoveries in the Philippines. FilipiKnow.com https://filipiknow.net/archaeological-discoveries-in-the-philippines/

Krieger, Herbert W. (1899). The Collection of Primitive Weapons & Armor of the Philippine Islands in the US National Museum. The Smithsonian Institution Bulletin 137.

Mallari, Perry Gil S. “Filipino Blade Culture and the Advent of Firearms,” (June 8, 2010). https://fmapulse.com/fma-corner/fma-corner-filipino-blade-culture-and-advent-firearms/

University of Michigan Library for their prints of individual pages from the Boxer Codex. https://apps.lib.umich.edu/online-exhibits/exhibits/show/translation-memory/a-historically-multilingual-sp