Why do millions of Filipinos work abroad? Because Filipinos have always done it—they have always migrated to work in other places—that is the shortest answer to that question. Migration has been a way of life for Filipinos as history bears out.

Migration in pre-colonial Philippines

Consider that that Philippines is an archipelago and long before the Spanish colonization, clans and bigger social groups called barangays had semi-nomadic existence. The earliest Filipinos had permanent riverine settlements during the dry summer months where they lived by fishing but when the rivers overflowed their banks during the wet season, the earliest Filipinos had alternative settlements in the hills where they hunted and gathered crops. They migrated to look for alternative shelters and alternative sources of food.

Migration through inter-island seafaring

From this, one can infer that the earliest Filipinos were accustomed to moving from place to place when weather conditions made it safer to move elsewhere and food sources became scarce. Consider, as well, that some islands are small and some groups of Filipinos lived on boats which could be docked in bays or at the mouths of rivers in bad weather or be used for inter-island voyages in good weather. The earliest Filipinos went on inter-island voyages for the purpose of barter and trade with both domestic and international merchants from India, China and Arabia long before the Spaniards came.

Migration through reduccion in colonial Philippines

When the Spaniards came, they forced the earliest Filipinos to settle in towns or poblaciónes where the church, the market and the municipal hall were located. This was called the reduccion—the forcible uprooting of whole swathes of populations from their farm lands to live in towns. Filipinos were required to live in the towns and shuttle to their bukid or farms riding their carabaos or their carretas.

Migration through the polos y servicios

The Spanish colonial government also conscripted Filipinos to engage in infrastructure projects such as building roads, churches and other government buildings. This conscription of labor was called polos y servicios. Filipino farmers had to stop farming when their services were required and render service to the Spanish crown wherever on the islands the building project was.

Migration through conscripted labor on the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade

The first instance of historically-recorded and official Filipino labor migration was in 1587. Spain regularly transported goods and raw materials between Acapulco, Mexico and Manila in what has been referred to in history books as the Galleon Trade. In 1587, a galleon landed in Morro Bay, California which was then still part of Mexico. The crew of the galleons included conscripted Filipino indios.

Spain colonized the Philippines because it was a source of raw materials such as rice, sugar, hemp and tobacco. In fact, Filipino farmers who grew food crops for their subsistence were required by the Spanish to grow cash crops instead. Unfortunately, the Filipinos were forbidden to sell their cash crops to anyone by the Spanish Crown as Spain had a monopoly on all the trade in cash crops on the islands. The cash crops were exported to Spain via Mexico.

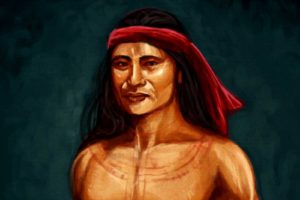

Filipino seafarers known as manilamen

As the galleon trade continued, more and more Filipinos participated: indios as crew members of the galleon and mestizos as investors and merchants on the galleon trade. The Filipino indios involved in the galleon trade were called manilamen. They werehighly regarded as knowledgeable seafarers and resourceful scouts and fishermen who supplemented the stored food for the voyage with their catch. In fact, Herman Melville in his novel, Moby Dick mentioned manilamen as part of the crew of the fishing vessel Pequod.

However, working conditions on the galleons were horrific, and it took four long months to cross the Pacific from Manila to Mexico. Crew members were underfed and they regularly succumbed to the effects of malnutrition: scurvy, beri-beri and other infectious diseases. It is no wonder that Filipino crew members usually deserted the galleons to settle among the Native Americans.

Filipino settlements in the Spanish Americas

Those manilamen who deserted the galleons taught the indios of Mexico how to distill tuba, a liquor made from coconut water. The Mexicans enjoyed tuba so much, they preferred it over the brandy dumped by Spain in Mexico. There was so much distilling of tuba by Filipino deserters in Mexico coastal areas that the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico banned the consumption of tuba altogether as it was rivaling the commerce in Spanish brandy.

By 1763, there were Filipino settlements in Saint Malo in Louisiana, a territory owned by the French in the Americas. The Filipino runaways felt safe enough to hide there from their Spanish overlords. In 1781, a Filipino indio by the name of Antonio Miranda Rodriguez Poblador was one member of the contingent sent by the Spanish crown to establish a settlement in Los Angeles in the California frontier of Mexico.

Migration of sakadas and pensionados during the American colonial period

After the 1989 Treaty of Paris when Spain relinquished the Philippines as its colony and ceded it to the US along with its territories in Mexico and Cuba, Filipinos were actively recruited by American companies to work as sakadas or agricultural workers for the fruit plantations in Hawaii, the fruit and nut farms in California and Washington state, and to work in the canneries in Oregon and Alaska. The novel by Carlos Bulosan, America is in the Heart, is the story of a boy who migrated to California as a fruit picker.

The American State Department also ran a student exchange program for deserving Filipino scholars who were called pensionados. Filipino scholars were usually scions of the Filipino ilustrado class, the middle-class mestizo Filipino families who were of mixed indio and Chinese or indio and Spanish ancestry. The US government sponsored their education at Ivy League schools in the US on condition that they return to the Philippines and either teach or else assist the US colonial government in the Philippines.

Migration as US Navy recruits, nurses, and war brides after World War 2

By the time the Second World War broke out, the US Air Force had built Clark Field as a training and storage facility and the US Navy had built Subic Naval Base. A lot of US servicemen worked out their tours of duty in the Philippines where they met and fell in love with Filipino women. After the surrender of Japan, the Filipino women who had married US servicemen were allowed to join their American spouses in the US to migrate as naturalized citizens.

The US Army and the US Navy also lost a lot of its soldiers and its ensigns. Filipino guerillas had proven their loyalty to the United States and so the Philippines became the recruitment sites. They recruited young Filipino men as infantrymen and navy stewards. The employment contract promised that those recruits would become naturalized citizens of the United States after completion of their training and tours of duty.

At the same time, a lot of veterans of the Second World War also came home wounded and injured, needing medical treatment, rehabilitation and ongoing medical care. US nurses who had served in World War 2 may have died in battle or may have come home wounded and injured themselves. There was a shortage of nurses in the United States. Since nurses in the Philippines had been trained by the US through the establishment of the Philippine General Hospital (PGH) and other district hospitals, Filipino nurses were recruited to work in the US as well.

Filipinos were already familiar with English since they had to learn English in the public school system established by the US in the early 1900s. Filipinos were accustomed to working for American bosses since American business enjoyed parity rights with Filipino businesses. Being colonial subjects for nearly 400 years first under the Spanish, then under the US and then under Japan, Filipinos had developed the temperament desirable in model colonial subjects which, in turn, made them good workers. Filipinos were compliant and subservient, easy to train and eager to please.

However, after the Second World War, former soldiers returning to the labor force had to compete with women who had been recruited to work in place of the men who went off the war. Americans then began to resent Filipinos and other Asian immigrants who also competed for jobs.

Migration of skilled workers to the US after 1965

The US passed the Tydings-McDuffie Law that limited Filipino migration to 50 every year. In 1946, the Luce-Celler Act increased the immigration quota for Filipinos to 100 every year. In 1965, the passing of the Immigration and Naturalization Act eliminated this quota, paving the way for an increase in Filipino migration to the US.The US limited Filipino immigration to professionals and to skilled laborers. Thus, Filipino doctors, nurses, engineers, accountants, teachers and soldiers migrated to the US.

Migration through the export of Filipino labor

In the 1970s, the Philippine economy under Martial Law was plagued with rising unemployment and dwindling foreign currency reserves. There were too few job opportunities and the government was bleeding dollars to pay for loans incurred by the Marcos government. Labor migration of Filipinos was endorsed by the Marcos government as a temporary strategy to solve those two problems.

In 1975, there were about 36,000 Filipino migrant workers who left for jobs in the Middle East. By 2013, there were 1.8 million Filipino migrant workers. During the term of Gloria Arroyo, the government expressed its target of sending 100,000 Filipino migrant workers abroad each year. This cemented the Philippines’ reputation as a “labor broker state.”

From the 1980s until the 1990s, Filipino men and women left to work in the Middle East as factory workers, construction workers, service crews such as waiters, cooks, cashiers and grocery clerks, nannies, maids and gardeners. Nurses, doctors, therapists and other healthcare professionals also left for jobs in the Middle East. Later, information technology workers, chefs and even teachers migrated for work. In 2003, the Global Labour Market Survey by the Seafarers International Research Centre estimate that 28.1% of all seafarers are Filipinos.

Permanent migration of Filipinos

As of now, an estimated 10 million Filipinos are labor migrants the world over. Some migrate permanently to first world countries such as the US, the UK, Canada, Australia, Germany, Japan and South Korea with the status of permanent legal residents that can later ripen into citizenship. When these labor migrants achieve permanent residency or citizenship their spouses, children and parents also migrate to join them. This estimated number does not include Filipinos who migrate as fiancées, partners, or spouses of nationals of those countries. Over all, the US is still the top destination of permanent Filipino migrants

Filipinos who permanently migrated in 2015 were estimated to have reached 100,000. Forty-one percent of these who permanently migrate were females within the age of 20-39. Twenty-one percent of these were children below 15 years old.

Temporary migration as OFWs

Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) who have a work contract approved by the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA) are considered temporary migrants because their labor contracts do not exceed twenty-four months. Filipino seafarers have contracts lasting 6-8 months. Of course, their contracts can be extended and renewed but generally, these temporary migrants will not achieve permanent resident status or citizenship in the country where they live or work. When their contracts expire, however, they may repatriate and enter new contracts of employment to work abroad again.

Irregular migrants as undocumented aliens

Irregular migrants are those Filipinos who leave the Philippines on a tourist or holiday visa but they work illegally or without a proper work visa. When their tourist visa expires, they return to the Philippines only to obtain another tourist visa in another country and work. Those who have been trafficked as sex workers or mail-order brides are among those who are classified as irregular migrants. Often, trafficked Filipino labor exit through the Philippines’ “back door” through Sabah.

Filipinos on a tourist or student visa to the United States but who do work without a proper work visa are often called TNTs an abbreviation of the Filipino phrase “tago ng tago” which describes their lives on the run from US immigration authorities, continuously hiding among their friends and relatives.

Labor migration as a way to increase family wealth

Polls show that about 20-29% of the adult Filipino population intend to migrate and work abroad. Children as young as eight years old express ambitions of working abroad when they are old enough. This is because labor migration is one sure way of increasing family wealth.

Labor migration as a way to increase national wealth

The Philippine government has mandated that all OFWs remit anywhere between 50-70% of their earnings to their families in the country. As of 1989, regular US dollar remittances reached one billion. Households use the dollar remittances to construct family homes, fund the education of children and other family members, increase savings and time deposit accounts, or start businesses.

Labor migration as replacement income

Interestingly, Filipinos from the countryside are migrating for work more than Filipinos in the cities. This is because Filipinos in the rural areas look at earnings from work abroad as a replacement for lost earnings in farming. The Philippines bears the brunt of natural disasters such as typhoons and earthquakes, drought and floods that cause crops to fail. When a farming family sends one of its members to work abroad, the earnings of that family member will help defray the cost of agricultural capital—buying farming land, buying farming implements and equipment, or purchasing seed.

Labor migration is an enduring Filipino way of life

What is interesting is that a poll of high school and college students showed that there are top three reasons why this group of young Filipinos want to work abroad: 75% of them say they want to send dollar remittances to their families to help them meet their needs; 72% said they wanted to experience other cultures; and 69% of them said they wanted to escape the lack of job and career opportunities in the Philippines.

Filipino migration for work is not new. Filipino labor has been exported as part of the policies of the powers that colonized the Philippines. Labor migration has also been sponsored by the Philippine government as a means to increase the influx of dollar remittances. On a personal level, Filipinos migrate because they have pressing family needs that cannot be met because of the lack of job and career opportunities in the country. But there are also other aspirational motivations for leaving the Philippines to work abroad—Filipinos want to see the world.

Sources:

Aquino, Belinda A. and Magdalena, Federico V. A Brief History of Filipinos in Hawaii. Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawaii. Available from: http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/hawaii-filipinos.html

Mojares, Resil B. “Tales of Manilamen,” Isabelo’s Archive. Anvil Publishing, 2013. pp 138-142.

Scalabrini Migration Centre. “The Philippines’ migration landscape.” Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development in the Philippines. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264272286-6-en.pdf?expires=1623294996&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=6C18DABC410F67B1A218E61726781E04

Stanford School of Medicine. Ethnogeriatrics. “Immigration History.” Available from: https://geriatrics.stanford.edu/ethnomed/filipino/fund/immigration-history.html

Very much appreciated. Thank you for this excellent article. Keep posting!