Jose Rizal was born on June 19, 1861 to Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonzo in Calamba, Laguna. From a young age, the Rizal showed love of learning and was considered precocious by his family that he was sent to a private tutor in the next town of Binan, Laguna. He later enrolled at the Ateneo Municipal, a secondary school run by the Jesuits.

“Rizal Shrine, Calamba” by tyroncaliente (incunabulus, formerly) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

He was artistic and excelled in poetry, painting, sculpture. When he was 18, he won a literary contest for his poem entitled A la Juventud Filipina (To the Filipino Youth). It was said that Rizal, a non-native Spanish speaker, submitted a poem in Spanish that was better than the poetry submitted by full-blood Spaniards living in the Philippine Islands. He also wrote a play El Consejo de los Dioses (The Will of the Gods) which was cited as the best entry in another literary contest but Rizal was not given the first prize because he was a Filipino (an indio and was neither a peninsular or an insular Spaniard—a peninsular was a Spanish subject born in Spain and living in the Philippines while an insular Spaniard was a full-blooded Spaniard who was born in the Philippines to parents who were Spanish subjects).

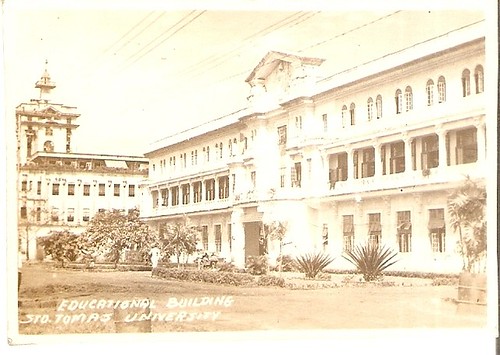

Rizal also studied at the University of Sto. Tomas, the royal and pontifical university of the Philippines which was run by the Dominicans. He then left for Spain to study medicine when he was 21 years old. While he was studying in Spain, he also learned French and German. He became friends with Filipino exiled in Spain and he wrote for a reformist newspaper named La Solidaridad. Rizal wanted civil rights and equal representation for indios (Filipinos) that the Spaniards had. He also wanted better education for Filipinos.

Rizal wanted civil rights and equal representation for indios (Filipinos) that the Spaniards had. He also wanted better education for Filipinos.

At the age of 26, his novel Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not) was published in the Spanish language in Spain. Very few copies of this novel reached the Philippines and even if it had, since it was written and published in Spanish, very few Filipinos would have read it. Rizal returned to the Philippines in 1887. While the novel was popular, it was banned by the friars in the Philippines because the novel was highly critical of Spanish friars in the Philippines.

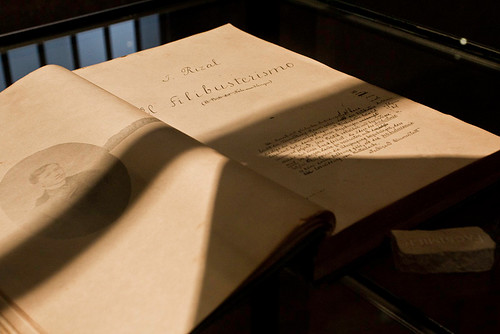

He left the Philippines once more. This second time, he wanted to study ophthalmology in Germany. While studying, he published his second novel, El Filibusterismo in 1891. This novel warned of a coming revolution. When he returned to the Philippines in 1892, he was banished by the Spanish colonial authorities to Dapitan. While he was there, he established a school for boys and practiced medicine. After four years of exile, he sought permission to leave the Philippines and travel to Cuba (another Spanish colony) and enlist as a military doctor.

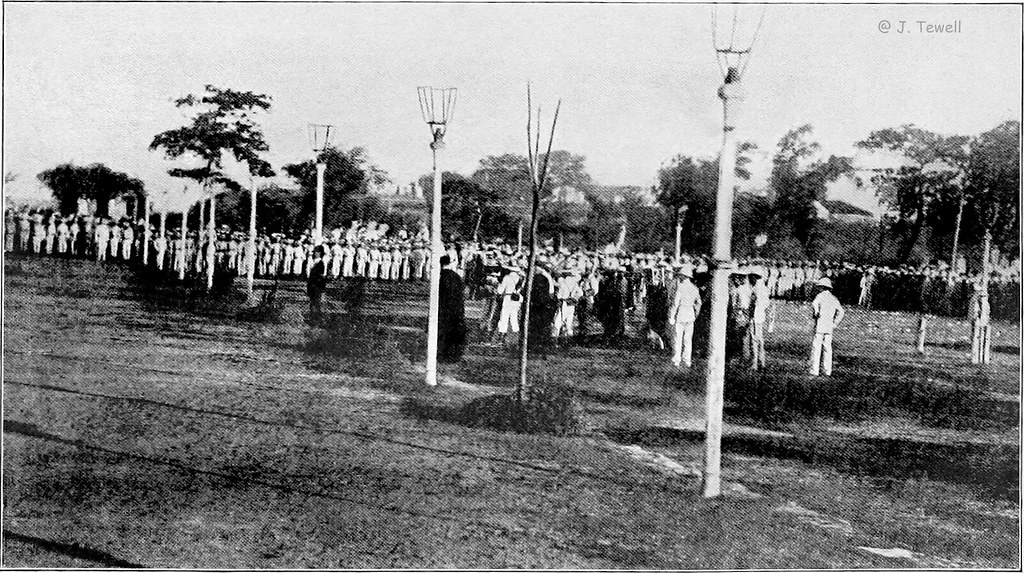

He was granted permission to leave the Philippines. He boarded a ship intending to travel to Barcelona when the Philippine Revolution broke out in 1896. Rizal never favored revolution, only reform. He also did not want to be involved in any revolution which was why he was traveling back to Spain. Before the ship could dock in Barcelona, Rizal was arrested and repatriated to the Philippines where he faced charges of treason and conspiracy in the revolution. He was later found guilty and was executed by musketry on December 30, 1896. He was only 35 years old.

On the eve of his execution, Rizal wrote his final poem, Mi Ultimo Adios, which was retrieved hidden inside a small alcohol stove and later given to his family. The poem consisted of 14 five-line stanzas written in Spanish. It revealed Rizal’s strong nationalism and love for his country.

It was ironic that Rizal, who objected to revolution, would be arrested, tried, and sentenced to death for starting a revolution. The drama of his escape, arrest and execution so captured the Filipino imagination that Rizal became a rallying point for the Philippine Revolution. He may not have wanted revolution but his death lit the flame for it.

It is also sad that after the Philippine Revolution against Spain, the United States of America came and colonized the Philippines. The Philippine Revolutionary War morphed into the Filipino-American War. For some, the Filipino-American War was the second act of an ongoing movement for independence.

Even the fervor whipped by the drama of Rizal’s execution could not sustain the Philippine Revolutionary Army which was ill-equipped. The U.S. Army, with its superior arms and superior military experience borne from the American Civil War and the war against Spain (for California, Texas and New Mexico), as well as the war against the native American nations, exhausted the Philippine Revolutionary Army.

As early as two years after Rizal’s execution, December 30 was marked as a national day of mourning. Rizal was held up as a representative of the brilliance of the Filipino. He was evidence that a person with brown skin can be every bit as intelligent and creative as a person with white skin. Every year of the American Occupation, Filipinos celebrated the birth of Rizal and commemorated his execution. Afraid that Rizal’s memory may ignite stronger patriotism among the exhausted Filipinos, William Howard Taft, the American civilian governor at the time, declared on June 11, 1901 that Rizal was the Philippines’ national hero.

Afraid that Rizal’s memory may ignite stronger patriotism among the exhausted Filipinos, William Howard Taft, the American civilian governor at the time, declared on June 11, 1901 that Rizal was the Philippines’ national hero.

Fifty-five years later, on December 30, 1956, President Ramon Magsaysay signed the Rizal Bill into law. This law required all Filipino high school and college students to study the works of Rizal. The compulsory study of the twin novels written by Jose Rizal was vehemently opposed by the Roman Catholic Church which condemned the works to be heretical. During his lifetime, Rizal was a Mason which made his anti-friar rhetoric in Noli Me Tangere understandably abrasive to the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines.

Rizal was reported to have made confession immediately prior to his execution and to have retracted his anti-church sentiments. Interestingly, El Filibusterismo ends with Crisostomo Ibarra, masquerading as Simoun the revolutionary, confessing his plans to plant a bomb and ignite a revolution. Simoun/Crisostomo Ibarra received absolution. This could mirror that change of mind that Rizal experienced toward the Catholic Church.

Whether Rizal truly repented of his anticlericalism and whether he returned to the faith from which he had become estranged, Rizal’s twin fictional works endure. Some commentators assert that the Noli and the Fili expressed the ilustrado (educated middle class) ideas of Rizal which did not reflect the yearnings of freedom of the mass of brown-skinned indios (Filipinos) who died fighting Spain and then the United States.

Critics agree that the twin novels captured an enduring literary snapshot of Philippine society in Rizal’s time. A century and a half later, the works continue to be studied not because the works are prophetic or eternally valid, instead, they continue to be relevant because contemporary Philippine society still mirrors Rizal’s depiction. The Philippines is still just waking up to its own sense of nationhood just as in Rizal’s Noli. The Philippines continued to be economically colonized by the parity rights enjoyed by the Americans even after Philippine independence. The Philippines was occupied by the Japanese during World War 2. And now, the Philippines is threatened by the economic and territorial incursions of China.

The “soft” imperialism of Hollywood and McDonald’s has left an indelible mark on the Philippines. And the masses of Filipinos—what of them? Just as in Rizal’s time, Filipinos continue to be indios bravos, an oppressed people, exiled and dispersed the world over as migrant workers, still yearning for freedom and equality.

Sources:

Agoncillo, Teodoro A. History of the Filipino People (Eighth Edition). C&E Publishing (1990). Pp. 145-148.

Anderson, Benedict R.O.G., Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1991.

Constantino, Renato. “Veneration without Understanding.”Third National Rizal Lecture, December 30, 1969.

Montes, Cristina A. “Rizal and the Catholic Church.” Philippine Daily Inquirer. June 16, 2018. https://opinion.inquirer.net/113955/rizal-catholic-church

Orosa, Sixto Y. Special Rizal Issue. Historical Bulletin, volume IV, number 2, (June 1960).

Laurel, Jose B. “The Trials of the Rizal Bill”. In Historical Bulletin, Special Rizal Issue, volume IV, number 2, (June 1960).