By Francesca Leana Jose

Cultural processes, traditions, values, and personal motivations influence the election of public officials and the rise and fall of ideologies. To properly understand the present state of Philippine politics, we must glance at the past.

Historical Context

Spanish Colonial Restriction

When the explorer Ferdinand Magellan came ashore on Limasawa in 1521, he came across the

indigenous form of governance called a karajahan or rajanate. On his mission to colonize what would become the Philippines, Miguel Lopez de Legazpi encountered the kadatuan, a feudal-based society. Both forms of government were smaller than those found in Europe, often encompassing only a swath or portion of an island.

Spain ruled the Philippines through the viceroy of Mexico but established on the islands a centralized colonial government headed by a governor-general appointed by the King. The governor-general appointed Spanish subjects as provincial officers. The Spanish crown did not consider the indios as citizens who had civil and political right at any time during their 330-year occupation. Thus, the indigenous population did not hold any elective political positions.

However, the indios instigated revolts, and in the later centuries of Spanish colonial rule, the Spanish crown allowed the principalia to hold office. The principalia comprised a class born from the intermarriage of the indio noble and educated upper classes with island-born Spaniards or immigrant merchant Chinese. They functioned as middlemen, reporting to the governor-general about the state of the indio majority. They held minor offices such as Cabeza de barangay, Gobernadorcillo, and El Teniente de Justicia. These were appointive offices and not elective.

American School of Democracy

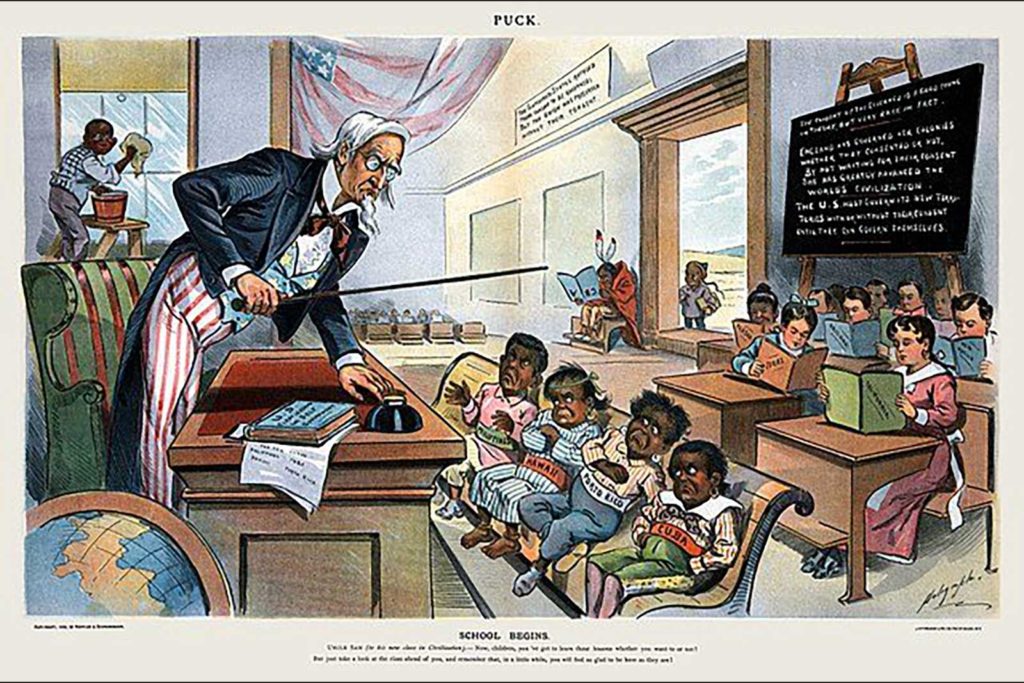

Elections were unheard of in the Philippines until the American colonial period, which began midway throughout the Philippine Revolution against Spain. The Americans came to the Philippines to extend the Spanish-American War that began with the Cuban rebellion in 1895. On December 10, 1898, the United States and Spain ended hostilities and signed the Treaty of Paris where Spain ceded Puerto Rico and Guam, Cuba became a protectorate, and the US purchased the Philippines from Spain and paid $20 million US dollars for the archipelago and its inhabitants.

American propaganda justified the occupation of the Philippines under the doctrines of Manifest Destiny and the White Man’s burden. The United States desired to shower on the Filipinos the blessings of democracy by tutoring them in American-style democracy. These claims are a rationalization of the US’s desire to gain a capitalist foothold in the Pacific and create a buffer zone in the event of worldwide warfare.

The US determined to make the Philippines a democracy in their own image. They promised to withdraw once their ‘little brown brother’ in the east can self-govern. In 1916, the US government created the Philippine Assembly, the first elective legislative body in Southeast Asia.

But Filipino leaders grew suspicious of the vague pledge of the 1916 Jones Act to recognize Philippine independence “as soon as a stable government can be established” when the US colonial government restricted the Philippine Assembly’s efforts at self-rule and continued to control the Philippines’ defense, foreign affairs, and trade. Prominent Philippine politicians pushed towards independence.

By 1933, the Philippine Legislature had sent a series of independence missions to Washington to push for a date of the grant of independence. Prominent politicians Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmena squabbled over who got the credit for independence even when they belonged to the same Nacionalista Party. The Tydings-McDuffie Act allowed a ten-year Commonwealth while Filipinos drafted their own constitution that would be subject to the approval of the US president.

In 1935, Manuel L. Quezon won the first national presidential election, and his election began the commonwealth period, the era also called the Peacetime, sandwiched as it was between the First and Second World Wars. During the Japanese Occupation that began in 1941, the Japanese installed a puppet government by appointing Chief Justice Jose P. Laurel as President. The Commonwealth ended on July 4, 1946, when Manuel Roxas was elected.

Cultural Context

Throughout Philippine political history, social and cultural mores dominated the Filipino psyche. Colonial mentality on matters of appearance, conduct, and creed is important in understanding modern Filipino politics.

Despite their best attempts, there is one glaring failure in the American democratic experiment in the Philippines: They failed to impart the two-party system. To this day, the tenets of conservatism and liberalism are not what most Pilipino voters look for in their candidates.

Personality-based politics

A candidate for an elective position needs more than a platform; a candidate must have fresh ideas, new perspectives, familiar affiliations, and above all, candidates must ooze charisma or appeal to draw attention and garner votes. Voters want someone like them or someone they admire or hope to be like in competence, capability, and accomplishments.

Physical beauty or the lack thereof affects appeal, but so do talents such as singing, dancing, or acting. Amiability may balance out a lack of pleasing features, but so will the right choice of clothing in cut and color.

Good public speaking is important, regardless of whether the candidate’s speech has substance. Proficiency and comfort in using English in speeches hint at higher education, which implies intelligence and the ability to represent the country internationally.

Which university or college the candidate graduated from is a factor. Whether the candidate graduated with honors adds points but being a member of a fraternity or sorority often means connections and financial support. But often, candidates with a rags-to-riches life story often make up for the lack of high educational attainment, political or social connections.

For candidates aspiring for a national office, they must cater to the deeply entrenched sense of regionalism within the Filipino psyche. Voters will more likely vote for a candidate who is from their hometown or home province because then, voters can make a personal connection, if necessary.

Name recall plays a large part in ensuring success in elections which also means that many seats in elective posts are won and occupied by actors, former actors, former news anchors, children of action stars, children of television evangelists, and scions of historically politically influential families.

Feudalism and political dynasties

Voters require concrete accomplishments: a road or bridge built, a port or railway system established. These are things voters look for. Voters judge politicians harshly when they cannot deliver on promises such as building a hospital or encouraging the establishment of businesses that will provide jobs. Whatever accomplishments a politician may claim, these have to be visible to gain votes. At the heart of this requirement for concrete accomplishments is patronage politics from the distant feudal past—elected officials enjoy public office only as far as they provide concrete benefits to their constituents.

The persistence of what is called the cacique democracy even in these modern times is proof of the intrinsic failure of the American democratic experiment. The principalia of Spanish colonial Philippines still occupy public office and hold political power today. Voters elect new local leaders based on the strength and accomplishments of a parent or sibling who formerly held the same elective position.

The family-centeredness of Filipino society expresses itself also in politics. Consider that the president Corazon Aquino won a popular revolution after her husband, Benigno Aquino Jr., was assassinated at the behest of the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos. Her son, Benigno Aquino III, was elected under the glow of his murdered father’s martyrdom and his mother’s demise.

As though history were repeating itself, 2022 presidential candidate Leni Robredo rose to political prominence upon the death of her husband Jesse Robredo, who was Secretary of the Interior and Local Government under Aquino III. She won the Vice Presidency in 2016. Trading on the same family-centeredness, the current mayor of Davao City, Sara Zimmerman Duterte-Carpio, will run for the vice presidency at the end of the term of her father, Rodrigo Roa Duterte.

Turncoatism and fluidity of party affiliations

The prevalence of personality politics and the lack of a clear and rigorous two-party system births turncoatism, which is called “balimbing politics”. A balimbing or star fruit has many sides. Thus, a candidate who easily switches party affiliation to further their ambition is commonly and derogatorily called balimbing.

It is common for elected officials in the House of Representatives, and the Senate, to abandon their current party and join the party of the newly elected president or at least create a coalition with it. On the local scene, mayors and governors join, leave or create their own parties as it suits the political climate. Personalities aspiring to launch their political candidacy often switch parties to put themselves in a better position when the election season comes around.

The fluidity of party affiliations often hinges on popularity. All politicians seek to ride a popular bandwagon as this will help their reelection. Switching to the newly elected president’s political party also gives the impression to voters that the candidates are willing to cooperate with those in power to press for the interests of their constituency.

Ideological differences rarely cause rifts in a political party in the Philippines. Instead, factionalism based on personalities often cause rifts. Party members choose to support party leaders who can promise funding and support from their machinery. Usually, rifts in parties are caused by the clash of political ambitions of the more influential or powerful members which causes less-influential party members to choose sides. Philipine politics does not turn only on ideological dominance; colonial historical, social, and cultural mores dictate how Filipinos play politics.

About the author:

Francesca Leana Jose is an Anthropology major at the University of the Philippines Diliman. The points at which history, society, and culture converge and influence each other are her research interests. She intends to take her master’s degree in cultural anthropology and heritage studies.